If you coach long enough, you’ll work with athletes or clients who have pain.

Not the kind that sidelines them completely, but the kind that lingers. Knees that ache. Backs that tighten. Shoulders that flare up every few weeks.

The question is: Should they still train?

According to current rehabilitation clinical practice guidelines, the answer is clear:

“Exercise is recommended as a nonpharmacologic intervention for musculoskeletal pain to improve pain modulation, promote healing through accelerated blood flow, and increase strength of muscles. Positive mental health benefits and improvements in pain-related fear and kinesiophobia are additional benefits of regular exercise.” — Wilson et al., 2025

That single paragraph says it all: movement isn’t just allowed in the presence of pain; it’s prescribed.

A recent review answers that with a clear yes, but with nuance. The authors, Wilson and colleagues (2025), lay out how exercise helps, when it might backfire, and how we can dose it better for those living with pain.

Why Pain Doesn’t Mean Stop

For years, the default advice was rest. If it hurts, don’t move.

But that model doesn’t hold up anymore. In most musculoskeletal conditions, such as chronic low back pain, tendinopathy, and arthritis, exercise is not only safe, but it’s also beneficial. Exercise can reduce pain sensitivity, improve function, and help athletes re-engage with movement.

The mechanism is something called exercise-induced hypoalgesia (EIH), the body’s natural pain-suppressing effect after exercise.

The catch? Not everyone experiences it the same way.

Some people get less pain after exercise. Others actually get more. And that difference isn’t purely physical; beliefs, expectations, and context shape it.

Why the Brain Matters as Much as the Body

One of the most powerful insights from this paper is that how someone perceives exercise influences how their nervous system responds to it.

In one study the authors highlight, a single bout of exercise paired with positive expectations increased pain thresholds by 22%. When the same workout was framed negatively, those thresholds dropped.

That means coaching language literally changes physiology. It’s a reminder that every cue, explanation, and check-in either calms or alarms the system.

While beyond the scope of this guide, it's important to note that pain is a personal output from the brain, based on many biopsychosocial factors. This is why damage alone doesn's explain the athlete's pain experience.

Building Safety Through Alliance

Pain often thrives on uncertainty. That’s why the therapeutic alliance, the trust and collaboration between coach and athlete, is critical.

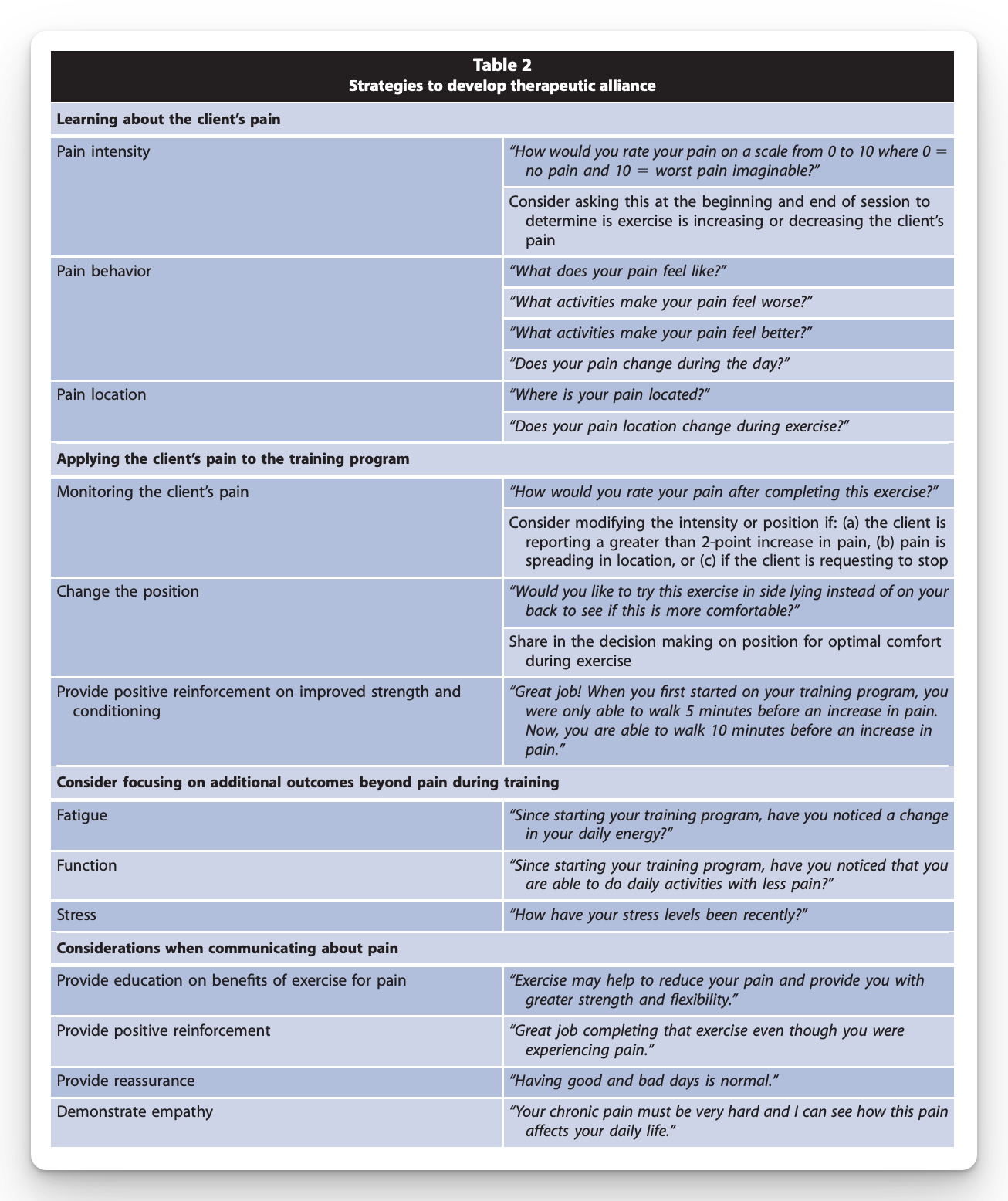

Ask about the pain:

- Where is it?

- What makes it better or worse?

- How does it behave during and after training?

When athletes feel understood, they’re more likely to keep showing up. And adherence, more than the perfect exercise or protocol, is what drives outcomes over time.

Strategies to Develop Therapeutic Alliance:

How to Program When Pain Is Present

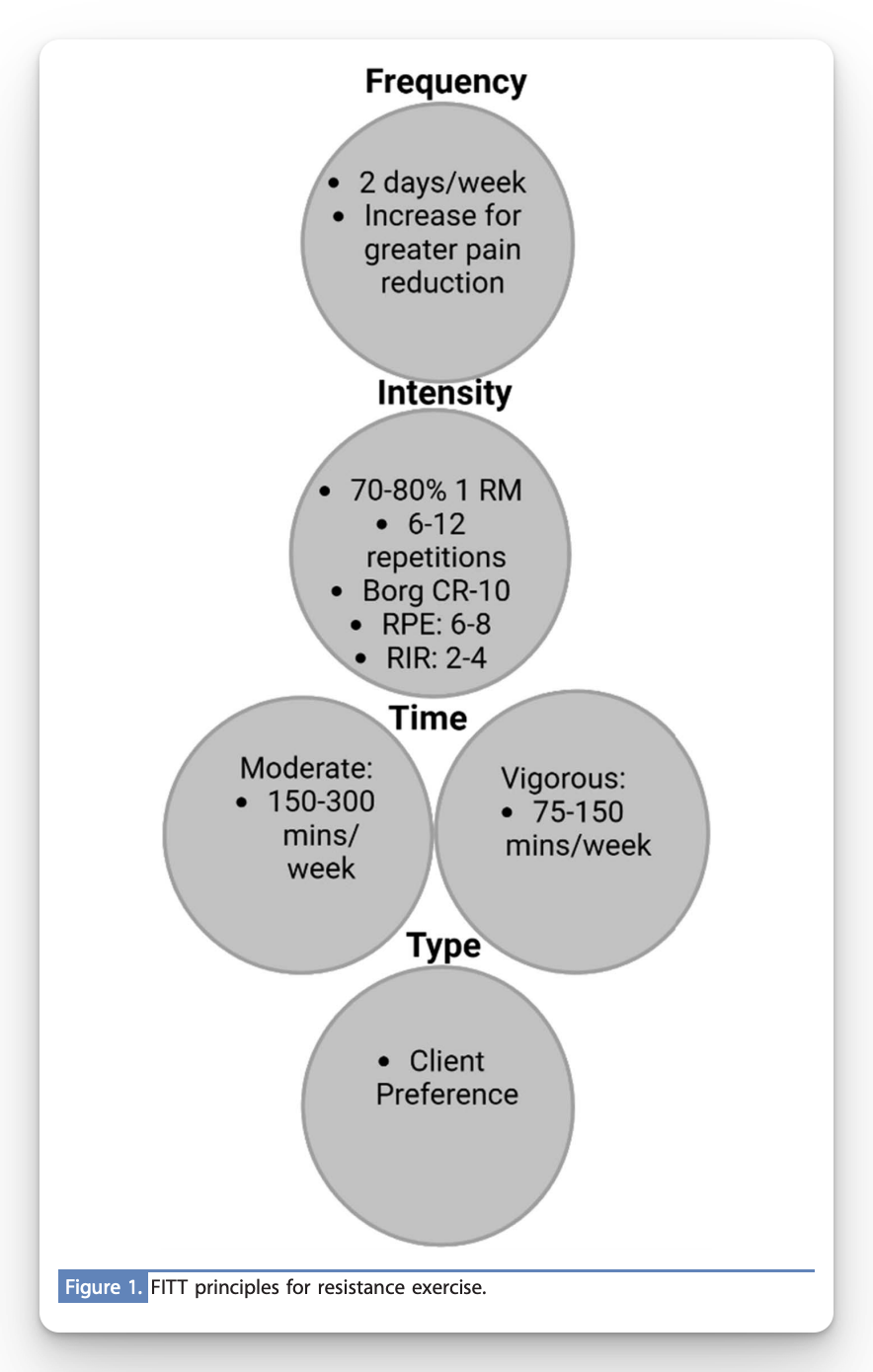

The authors provide practical FITT (Frequency, Intensity, Time, Type) guidelines that translate directly to the weight room or court.

1. Frequency and Time

Aim for consistency. Short, frequent sessions are more effective than one big weekly grind.

- 150–300 minutes per week of moderate activity

- or 75–150 minutes of vigorous activity

If pain is high, break those into smaller doses—10–15 minutes at a time—and build up.

2. Intensity

- Resistance training: Moderate to high loads (70–80% 1RM) can be beneficial even in low back pain—if tolerated.

- Aerobic training: Moderate intensity works well, but higher intensities might produce a stronger pain-reducing effect in those who can tolerate it.

Use RPE or reps in reserve (RIR) to autoregulate. If pain increases more than ~2 points or spreads, modify position, range, or load.

3. Type

Every form of exercise has value. The “best” one is the one the athlete enjoys and can perform consistently.

- Resistance and core-based programs slightly outperform others for pain and disability.

- But variety and choice improve buy-in and long-term adherence.

FIIT Guidelines:

Coaching Language That Changes Pain

A small script can go a long way:

“Exercise can actually help reduce your pain and build your tolerance over time. We’ll start with what you can do comfortably and progress as your body adapts.”

This primes the athlete for success. It sets an expectation that pain is not damage and that movement is safe.

What Success Looks Like

When coaching pain, the goal isn’t always “pain-free.” It’s “function first.”

You want the athlete to move more, sleep better, and build confidence in their body again. Over time, the pain usually follows.

Progress can be tracked in several ways:

- Increased training volume or load tolerance

- Improved mood, sleep, or recovery

- Less fear of specific movements

Pain is a lagging indicator. Function and confidence lead the way.

Limitations and Reality Checks

Not every person responds to exercise the same way. The research is clear: there’s no universal formula for intensity or mode.

Those with nociplastic pain, pain that’s more neural than structural, often need a slower ramp-up and more focus on education and reassurance.

And because most studies rely on short interventions, we still lack clear long-term dose-response data. But the overall signal is consistent: movement helps, mindset matters.

Takeaway for Coaches and Clinicians

When an athlete says, “It hurts,” your job isn’t to pull the plug. It’s to create a plan that builds safety, tolerance, and belief.

- Coach the context and explain why exercise helps.

- Dose by tolerance, not fear.

- Win with frequency and consistency.

Training in pain isn’t reckless; it’s rehabilitation done right.

I hope this helps,

Ramsey

Reference: Wilson AT, Lyons K, Yapp-Shing C, Hanney WJ. Train in Pain: A Review of Exercise Benefits and Application for Individuals With Musculoskeletal Pain. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 47(1), 2025.