Everyone knows the story of the tortoise and the hare.

The hare explodes out of the gate, looks dominant early, and grabs everyone’s attention. The tortoise moves slowly, never looks impressive, and gets ignored.

Then, over time, the tortoise keeps going while the hare fades.

In sports, we often focus on the hare. But compelling new data suggests we should be searching for the tortoise.

In a 2025 review published in Science, Güllich and colleagues examined nearly 35,000 adult international top performers across sport, chess, music, and science.

Instead of focusing on youth success, they asked a more important question:

Do early standouts actually become world-class adults?

Early stars and elite adults are usually different people

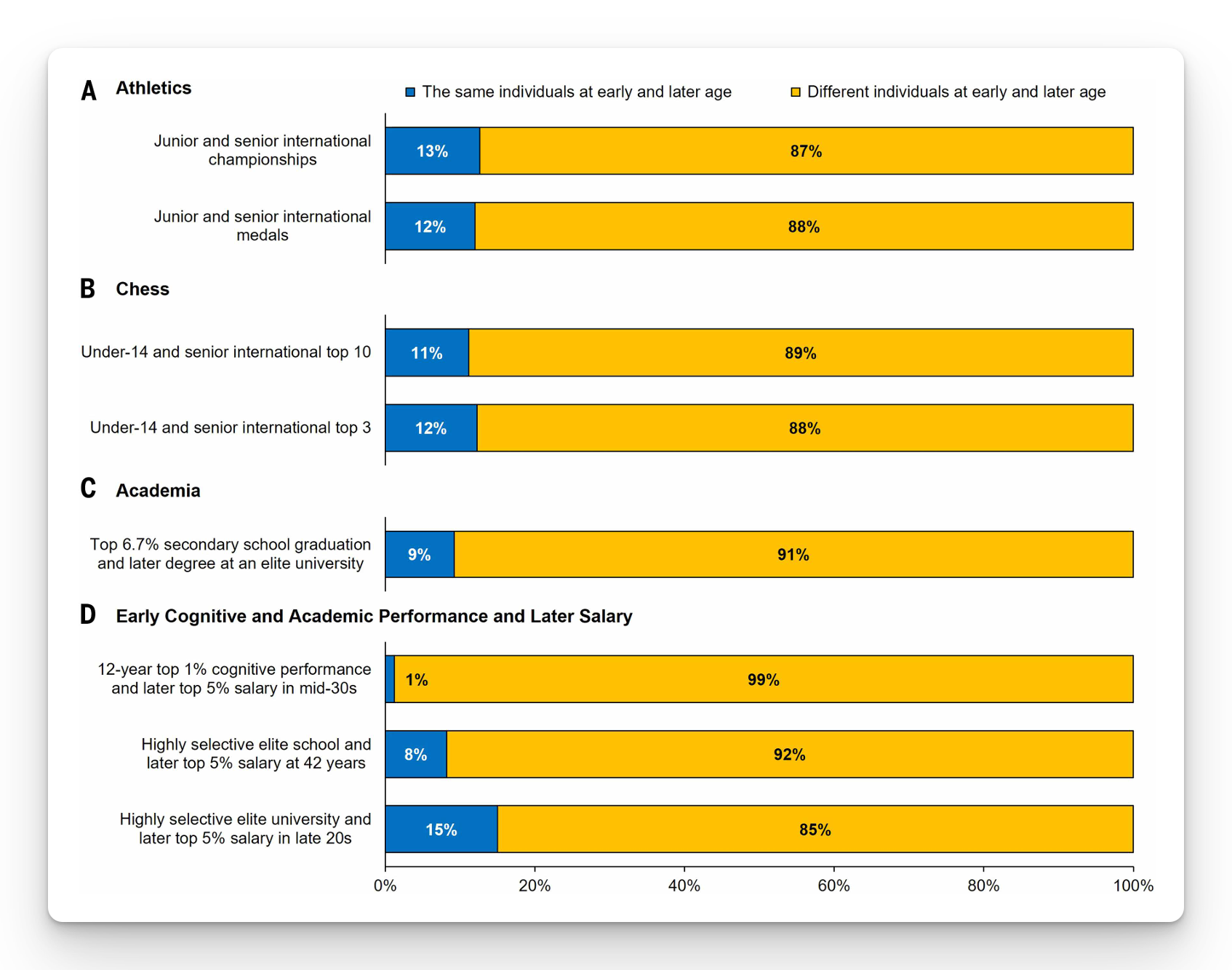

Across multiple domains, the answer was surprisingly consistent.

- The majority of world-class adults were not top performers as juniors.

- In several datasets, around 85 to 90 percent of the athletes who reached the highest adult levels were not early stars.

This does not mean early success is meaningless. It means early success is a weak predictor of long-term excellence. Winning early often reflects early physical development, opportunity, or access, not necessarily future potential.

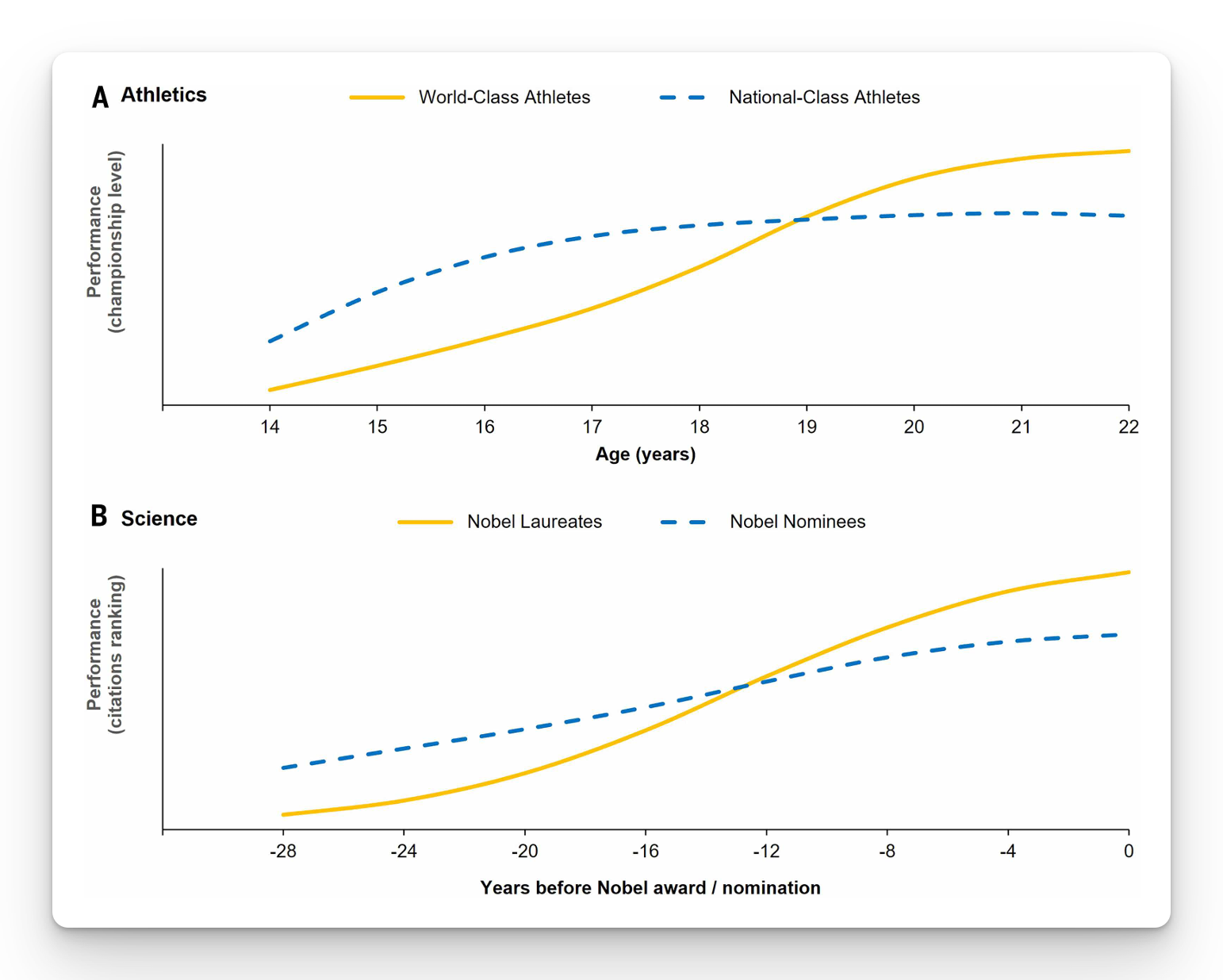

At the very top, the pattern flips

When researchers compared world-class adults to those just below them, early performance sometimes showed a negative relationship with peak performance. In plain terms, some of the very best adults were less impressive early on than those who never reached the same level later.

Slower early progress was not a flaw. It was a common feature. This is the tortoise pattern showing up in real data.

Why “more and earlier” stops working

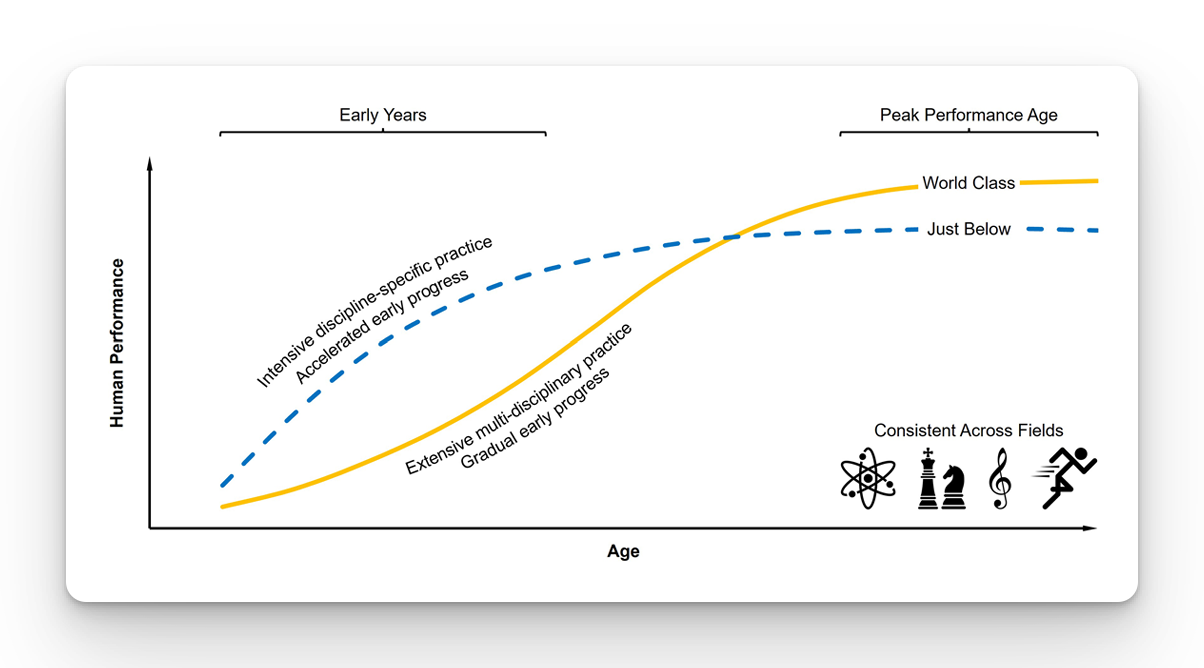

What predicts early success is not the same as what predicts ultimate success.

Earlier specialization and more sport-specific practice often help at youth levels, but those same traits lose power when the goal becomes world-class adult performance.

The highest-level adults tended to show more gradual early development, less early sport-specific practice, and more exposure to multiple sports or disciplines. That does not mean they trained less. It means their development was spread out rather than compressed.

Gradual development can be beneficial for a few reasons:

- Broader early exposure increases the chance of finding the right fit.

- Multi-sport experiences appear to build adaptability and learning capacity.

- Slower early progression also reduces burnout, overuse injury, and dropout, allowing athletes to stay in the system long enough for talent to emerge.

What this means for coaches

Early dominance is easy to spot, but it is not destiny.

Trajectory matters more than snapshots. Athletes and performers who keep improving, stay healthy, and adapt over time often have higher ceilings than those who peak early.

The hare always looks better at the start. The tortoise just keeps showing up. Across disciplines, from sport to music to chess to science, the long game wins.

I hope this helps,

Ramsey

Reference

Güllich, A., Barth, M., Hambrick, D. Z., & Macnamara, B. N. (2025). Recent discoveries on the acquisition of the highest levels of human performance. Science, 390, eadt7790.