Almost three decades ago, The Notorious B.I.G. warned us: “Mo Money Mo Problems.” In sport, it translates perfectly. The more output an athlete can generate, the more load, fatigue, and injury risk comes with it.

As coaches, we love athleticism. We love strength, speed, power, explosiveness, and every attribute that sits on the “performance” side of the ledger.

But hidden underneath the impressive physical displays is something every performance professional needs to understand:

The same qualities that help athletes dominate can also increase their risk of breakdown if the system around them cannot support those outputs.

More strength means higher forces. More athleticism means more speed, more stress, and more load. More fast-twitch muscle means more peak power, but also more fatigue and slower recovery.

Let’s walk through a few studies that outline what I call the Performance-Injury Paradox.

Study 1: Higher Vertical Jump at the NBA Combine, Higher Likelihood of Future Surgery

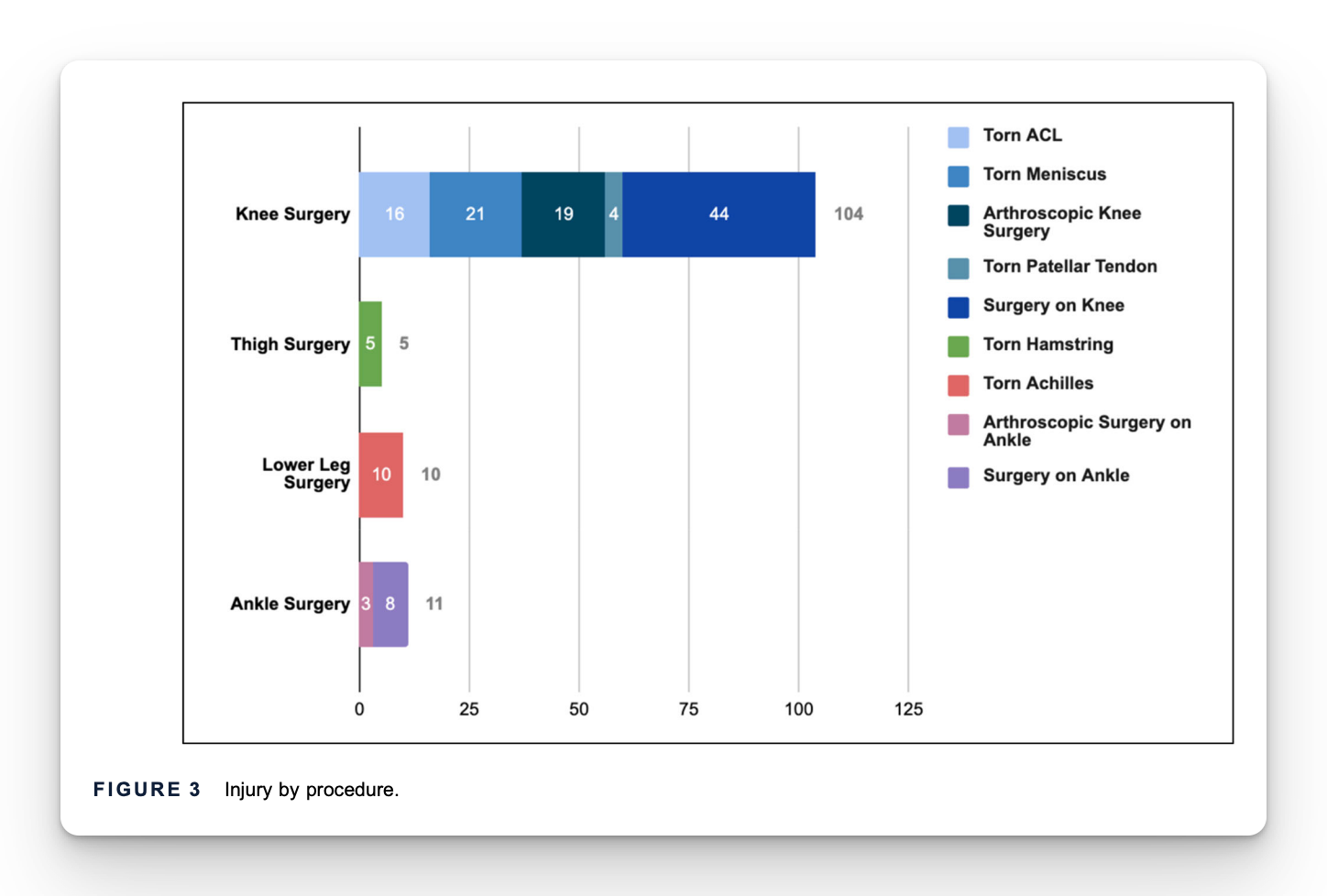

Patel et al. (2025) examined 10 years of NBA Combine data and linked it to future lower-limb surgeries.

Key Finding:

Players who later required surgical intervention had higher standing and max vertical jumps at the combine.

No differences in sprinting, agility, or anthropometrics. Only vertical jumping separated those who stayed healthier from those who needed surgery.

The knee was the dominant surgical site (80%). Players who jumped higher earlier in their careers ultimately ended up on an operating table at higher rates.

Interpretation:

High-output athletes place more load through the knee during takeoffs, landings, and cutting. That means more stress per repetition and less margin for technical inefficiency or periods of overload during play.

Athleticism raises the ceiling on performance and the floor on required durability.

Study 2: Stronger Shoulders, More Shoulder Injuries

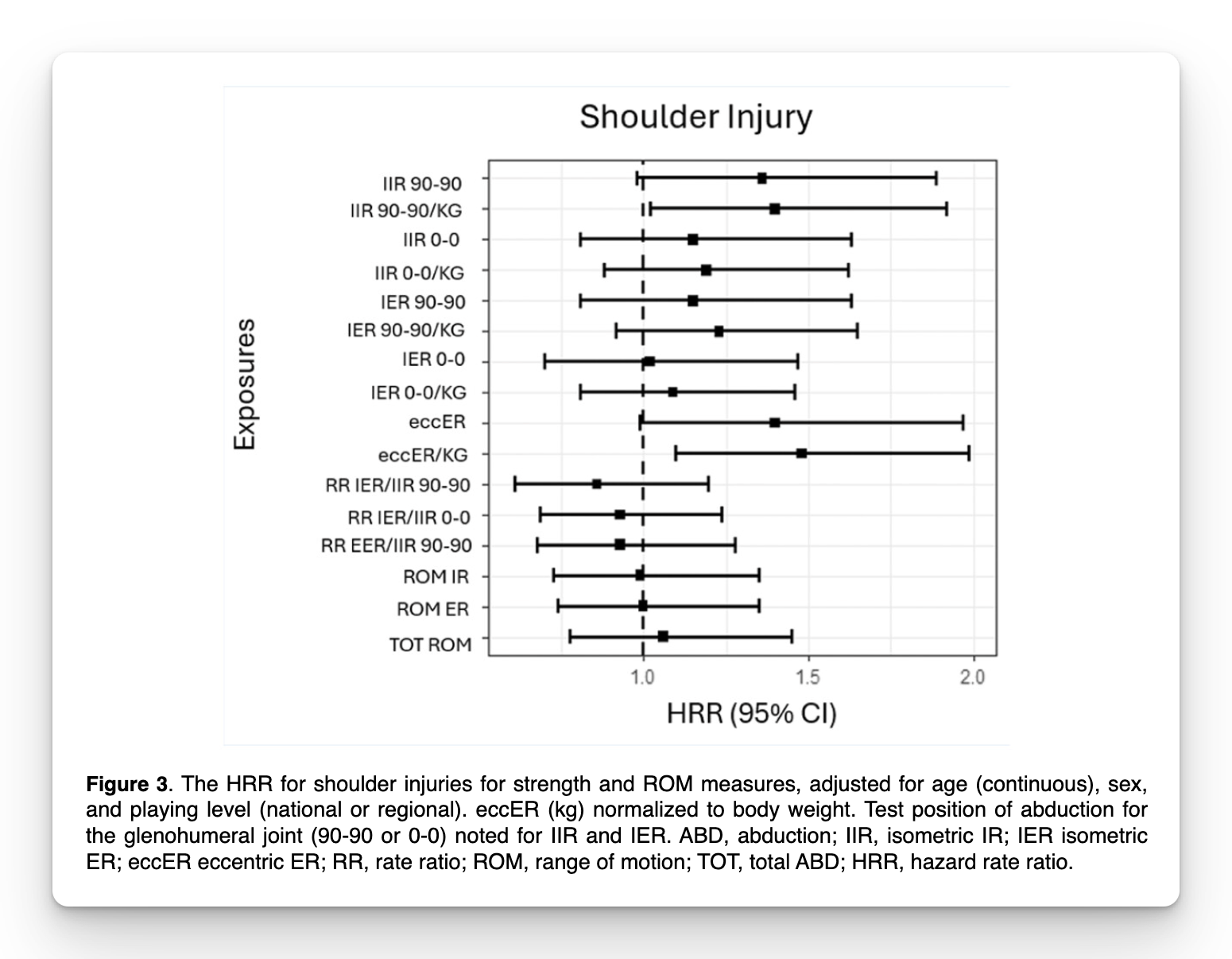

Johansson et al. (2025) followed 301 competitive adolescent tennis players for 12 months and tested eccentric and isometric rotator cuff strength and passive ROM.

Key Finding:

The athletes with greater eccentric external rotation strength and greater isometric internal rotation strength in the 90/90 position had a higher risk of substantial shoulder complaints and injuries over the next year.

Not lower risk. Higher.

This challenges a common assumption that stronger tissue is more robust.

In growing athletes, increased strength may mean higher serve speeds, higher racket forces, and greater overall exposures that their tendons and joints cannot yet support.

Interpretation:

Strong muscles can create loads that outpace the rate at which passive tissues adapt. Without thoughtful progression of volume, especially in developing athletes, strength can outpace durability.

Study 3: Fast-Twitch Athletes Fatigue More and Recover Slower

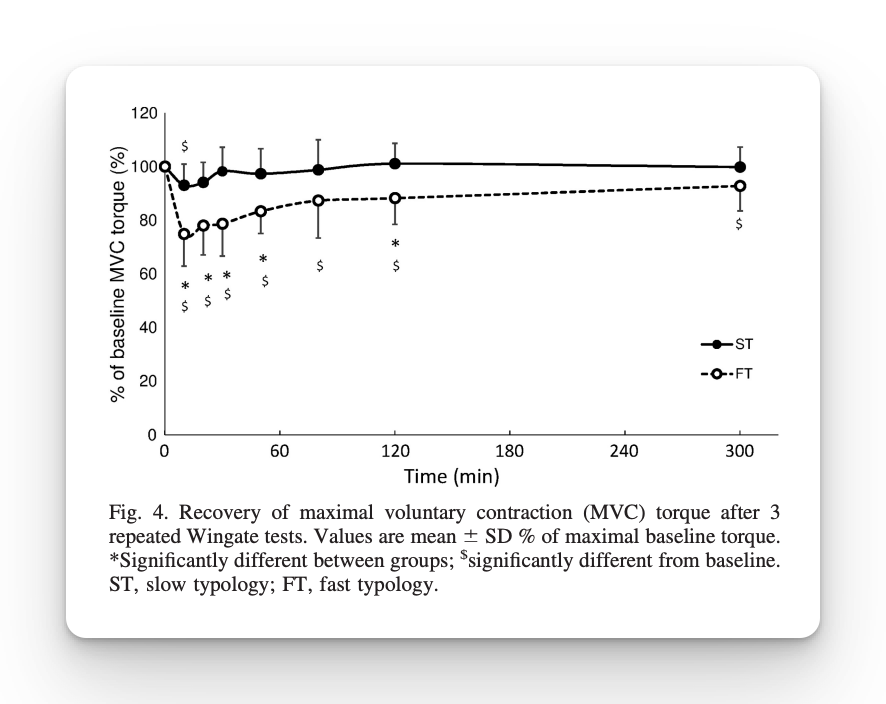

Lievens et al. (2020) used a noninvasive method to determine fiber-type makeup and then put “fast-twitch dominant” (FT) and “slow-twitch dominant” (ST) athletes through three Wingate tests.

Key Findings:

- FT athletes had a 61% power drop, compared to only 41% in ST athletes.

- ST athletes fully recovered knee-extensor torque within 20 minutes.

- FT athletes still hadn’t recovered after 5 hours.

Fast-twitch muscles provide the horsepower, but the cost is high fatigue and long recovery timelines.

Interpretation:

Even when producing the same total work, FT athletes experience more peripheral fatigue, more contractile impairment, and slower restoration of force-producing capacity.

Performance Capability Must Be Matched With Capacity

Across all three studies, a pattern emerges: higher performance comes at a cost. And if these costs are not accounted for, risk can rise.

Click play and the video will start where I breakdown the performance-injury conflict

The common denominator is not strength or athleticism. It is the absence of systems that scale load appropriately for the athlete’s output capacity.

Stronger athletes hit harder, jump higher, accelerate faster, and expose their tissues to more stress per movement. If volume, density, recovery time, and tissue preparation don’t scale with those outputs, the risk curve bends the wrong direction.

Here’s what coaches need to consider:

1. High-output athletes require more intelligent load management

These athletes can tolerate higher loads from a muscular standpoint, but passive structures may lag. Progressions must be slower, volume must be tracked more carefully, and big weeks need to be supported with intentional recovery.

2. Strength and athleticism don’t automatically equal resilience

Study 1 and 2 show this clearly. Capability without capacity creates risk.

A 14-year-old with elite serve velocity may be “too strong for their own good” if their tendon quality, ROM, and growth status aren’t ready for those loads.

A 19-year-old NBA prospect with a 40-inch vertical has massive upside, but also massive force spikes on every landing.

3. Fast-twitch athletes are the “high-maintenance Ferraris” of sport

They produce big outputs and need more recovery between exposures. Your fast-twitch athletes will:

- fatigue faster

- recover slower

- accumulate stress quicker

- require more spacing between high-intensity days

- be at greater risk during congested schedules

This is physiology, not mentality.

4. The goal is not just building horsepower, but building the chassis

To do this, coaches should invest more time in:

- tendon conditioning

- deceleration capacity

- isometric and eccentric strength

- controlled exposure to higher volumes

- recovery systems scaled to athlete type

Otherwise, strength and athleticism reveal cracks rather than create advantages.

Coach's Takeaway

Strength, speed, power, and fast-twitch physiology are performance multipliers.

They are also load multipliers.

Athletes with these traits aren’t fragile. They simply operate at intensities that demand more intelligent planning.

The lesson isn’t to avoid chasing strength or athleticism.

The lesson is that without thoughtful load management, the very qualities we develop to enhance performance can also accelerate injury and fatigue.

I hope this helps,

Ramsey

References

- Johansson, F., Batt, M. E., Ellenbecker, T., & Skillgate, E. (2025). Association between eccentric and isometric shoulder rotation strength, shoulder range of motion and injury incidence in the shoulder in adolescent competitive tennis players: The SMASH cohort study. Sports Health.

- Patel, R. A., Shah, R. M., Hauer, T. M., Terry, M. A., & Tjong, V. K. (2025). National Basketball Association combine scores as a predictive measure of lower limb surgery over 10 consecutive seasons (2010–2020): A retrospective review. Journal of Experimental Orthopaedics, 12, e70336.

- Lievens, E., Klass, M., Bex, T., & Derave, W. (2020). Muscle fiber typology substantially influences time to recover from high-intensity exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology, 128(4), 648–659.