Tendinopathies suck.

Jumpers with patellar pain. Runners battling Achilles symptoms. Lifters who can’t press without elbow irritation. These cases are common, stubborn, and rarely solved by just “resting it.”

As coaches, we need to understand what’s actually happening inside the tendon so we can manage load intelligently rather than guess.

Millar et al. (2020) published an excellent review appropriately titled Tendinopathy. It’s one of the most comprehensive summaries of the biology, mechanics, and management of tendon pain.

Here are five key takeaways that should influence how you coach.

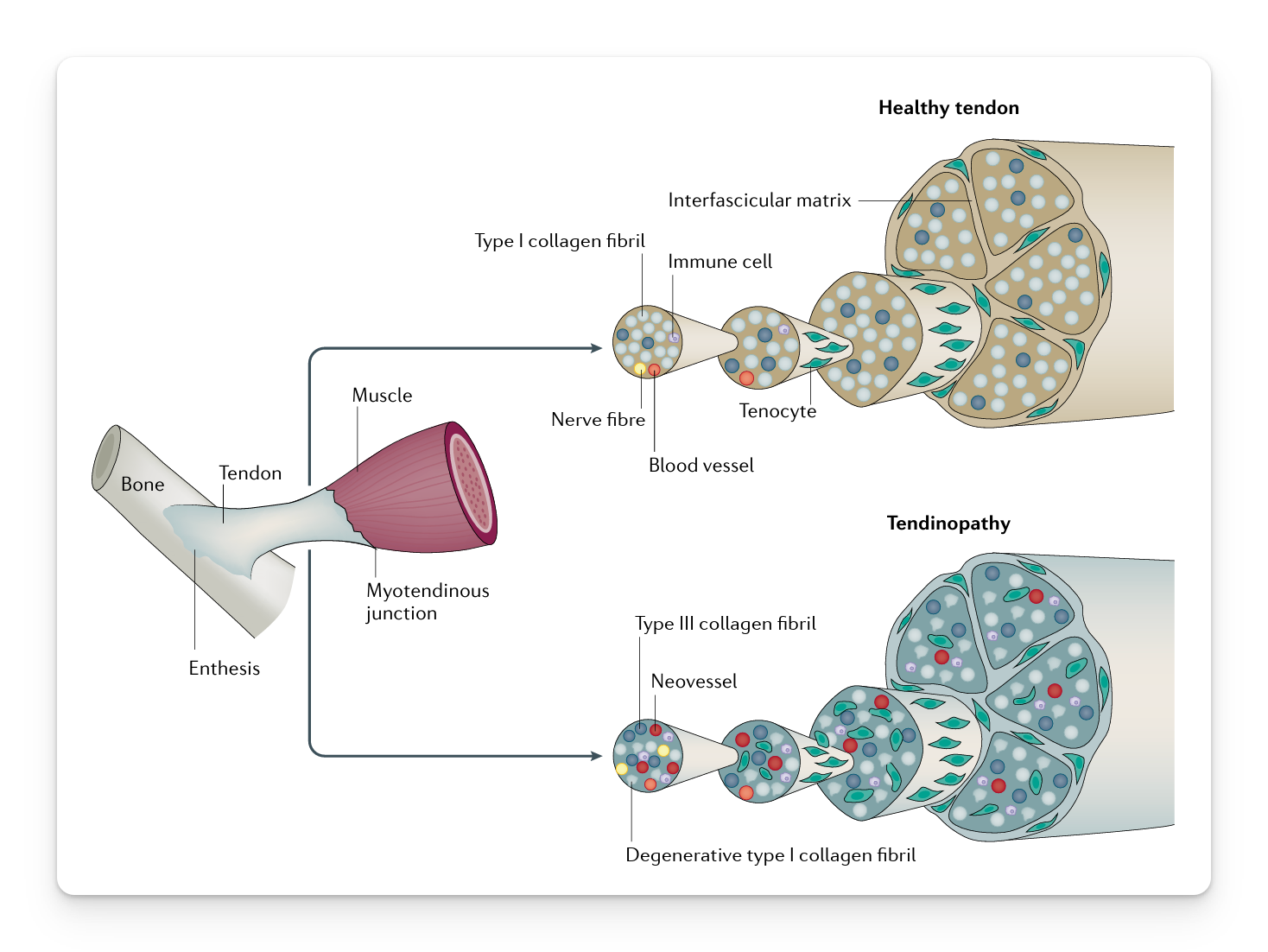

1) It’s Not Just Inflammation

The old model labeled everything “tendinitis,” implying inflammation was the primary issue.

In chronic tendinopathy, that’s usually not true.

What researchers consistently see:

- Disorganized collagen fibers

- Increased ground substance

- Structural thickening

- Changes in cellular activity

This is remodeling, not classic inflammation.

Why it matters: if the problem is structural adaptation and load tolerance, then anti-inflammatories and passive modalities are not the main solution. Progressive loading is.

2) Imaging Does Not Equal Pain

One of the most important practical insights:

Structural abnormalities are common in asymptomatic athletes.

In other words:

- An athlete can have a “bad-looking” tendon and no pain

- An athlete can have significant pain with modest structural findings

Pain is influenced by mechanical stress, neural sensitivity, and load exposure history. Structure is part of the picture, but not the full story.

As a coach, this means return-to-play decisions should prioritize:

- Symptom response to load

- Functional performance

- Tolerance over time

This is why its often said "treat the athlete, not the image."

3) Load Is the Problem and the Solution

Tendinopathy is strongly associated with:

- Rapid increases in training load

- High cumulative tendon stress

- Insufficient recovery

In simple terms, load exceeded capacity.

But unloading the tendon completely is rarely the fix.

Tendons adapt to mechanical strain. They require progressive stress to remodel and regain tolerance.

Evidence supports:

- Heavy slow resistance training

- Eccentric-based programs

- Gradual progression of tendon strain

- Isometrics for short-term pain modulation

Load is medicine. The key is dosage and progression.

4) Tendons Adapt Slower Than Muscle

This is where many programs unintentionally create problems.

Muscle strength can increase quickly. Output improves. Force production rises.

Tendon adaptation lags behind.

If you build force capacity rapidly without respecting tendon timelines, you create a mismatch. The muscle can generate forces the tendon is not yet prepared to tolerate.

This commonly happens during:

- Aggressive offseason strength blocks

- Preseason ramps

- Return to play after layoffs

Smart programming acknowledges this adaptation gap and progresses high-strain activities accordingly.

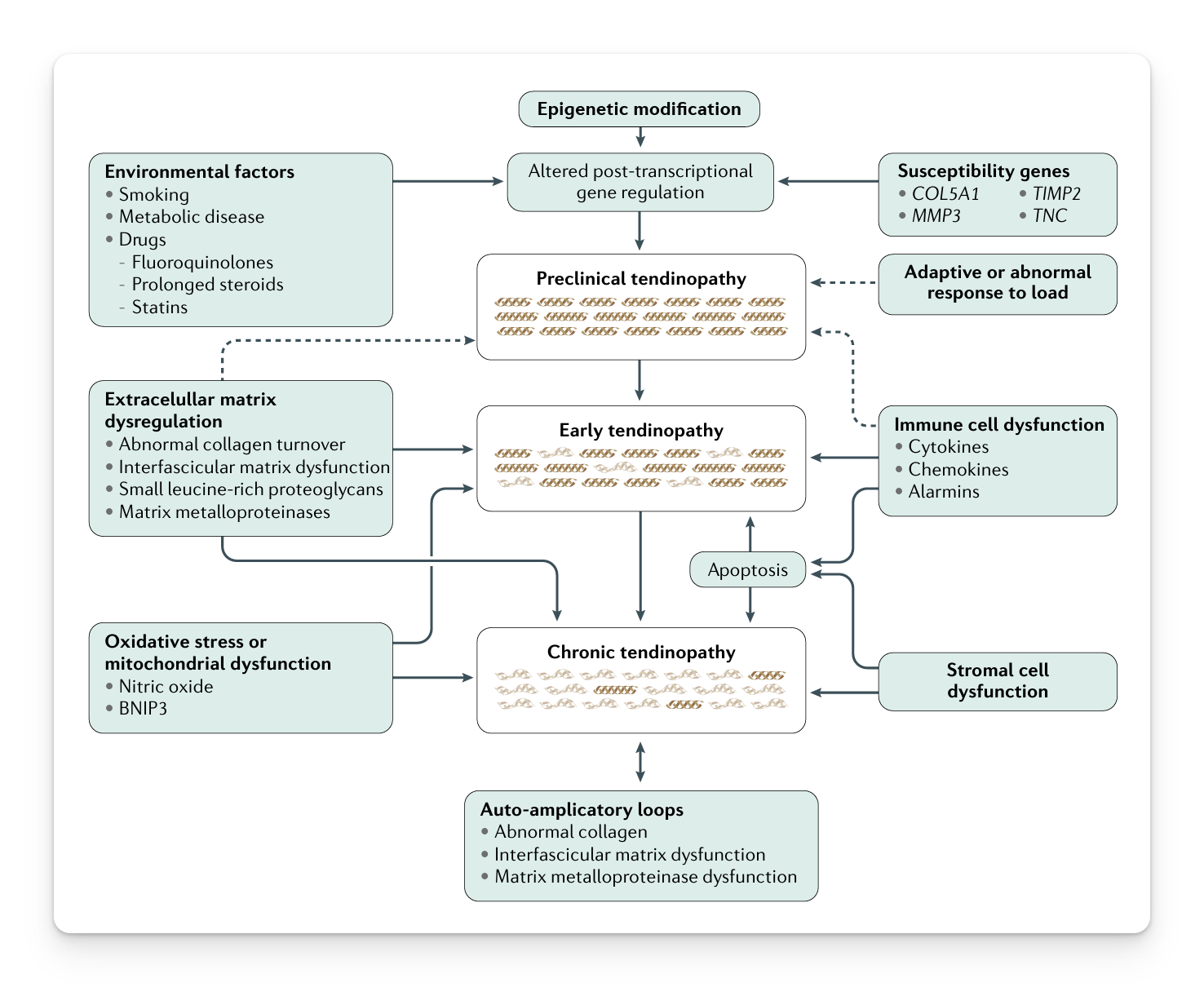

5) Capacity Is Multifactorial

Tendinopathy rarely has a single cause.

Risk factors include:

- Previous tendon injury

- Load spikes

- Strength deficits

- Age-related changes

- Biomechanical inefficiencies

- Systemic health factors

Most cases are cumulative.

The coaching question becomes: Did workload outpace tissue capacity?

That’s a programming and monitoring issue. And that’s something we can influence.

Takeaway for Coaches and Therapists

Tendinopathies are frustrating because they sit in the gray zone. Not acute enough to shut everything down. Not minor enough to ignore.

But they are not random. They usually result from load exceeding capacity over time.

Millar et al.’s review reinforces a simple principle for coaches:

- Respect load progression

- Build strength deliberately

- Accept that tendon adapts slower than muscle

- Use progressive loading as your primary intervention

When you understand that tendinopathy is fundamentally a load management challenge, your approach becomes clearer, calmer, and far more effective.

I hope this helps,

Ramsey

Reference

Millar NL, Silbernagel KG, Thorborg K, et al. (2020). Tendinopathy. Nature Reviews Disease Primers.