Drop jumps are everywhere in performance programs. And the current trend seems to be "higher drops is better."

The problem is, that's not right. Previous research shows higher drop heights don’t always improve jump performance, but they do increase joint loading and injury risk. We have addressed this at length here.

This study addressed that problem by prescribing drop jump heights as fixed percentages of each athlete’s countermovement jump height (50–150% CMJ), allowing the researchers to examine how increasing relative drop height altered landing mechanics and performance.

When drop jumps are prescribed relative to CMJ height, do higher drops enhance performance, or do they simply increase landing forces and braking stress?

What Did the Researchers Do?

Participants

- 20 Division I male volleyball players

- Highly trained, frequent jumpers

- ~8 years of training experience

Protocol

- Athletes performed 3 maximal CMJs

- Their average CMJ height was calculated

- Drop jump heights were set relative to the athlete's CMJ: 50%, 75%, 100%, 125%, 150% CMJ height

- Athletes performed 3 DJs at each height

- Motion capture (200 Hz) and force plates captured full biomechanics

What Variables Were Measured?

Performance

- Drop jump height (DJH)

- Ground contact time (GCT)

- Reactive Strength Index (RSI)

Landing Demands

- Peak ground reaction force (GRF)

- Landing impulse

- Incoming velocity and kinetic energy

- COM landing depth

Joint Mechanics

- Hip, knee, ankle power absorption

- Negative joint work during landing

What Were the Results?

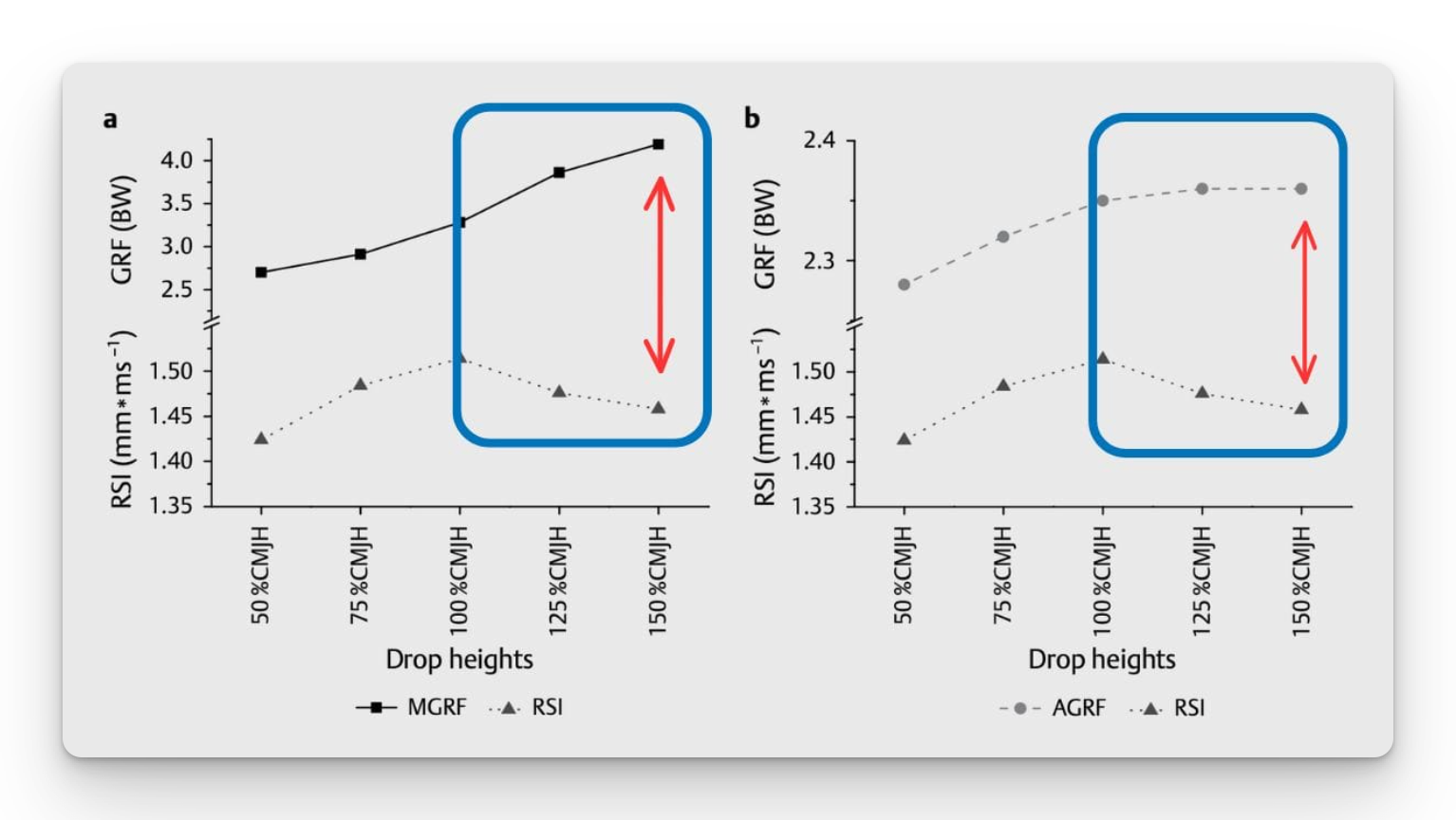

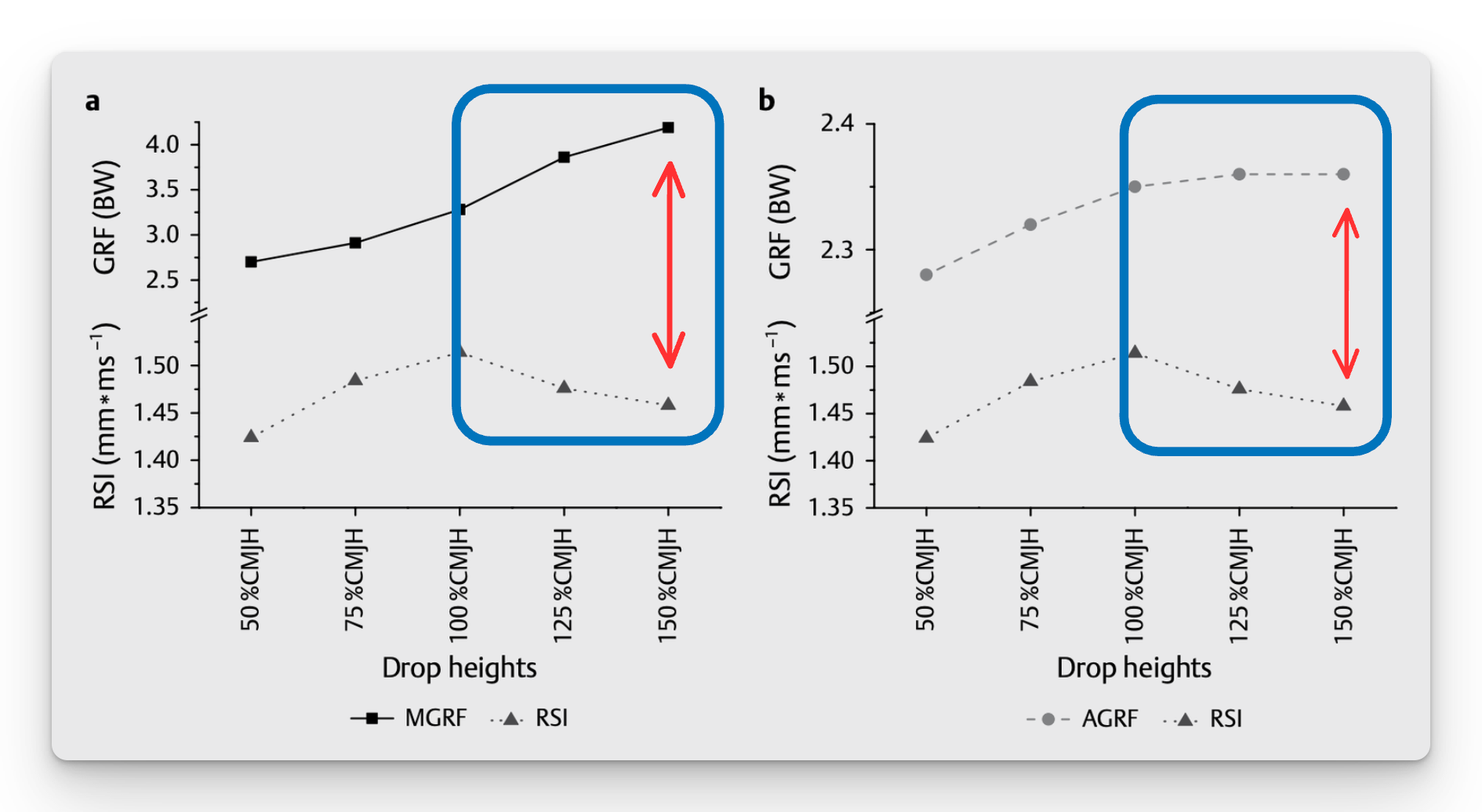

Jump Performance Was Unchanged Across Drop Heights

- Drop jump height showed no meaningful differences

- Ground contact time remained stable

- Reactive Strength Index did not improve

Across all conditions, from 50% to 150% of CMJ height, increasing drop height did not enhance jump performance.

Landing Forces Increased Aggressively Past 100% CMJ

Once drop height exceeded 100% CMJ:

- Peak GRF jumped sharply

- Landing impulse increased

- Incoming velocity and kinetic energy skyrocketed

At 150% CMJ:

- Peak GRF approached 4x bodyweight

- Landing impulse increased up to ~25%

More Height = More Braking, Not More Output

As drop height increased:

- COM dropped deeper

- Athletes spent more time and energy absorbing force

- But did not convert that energy into better propulsion

This is classic attenuation without utilization.

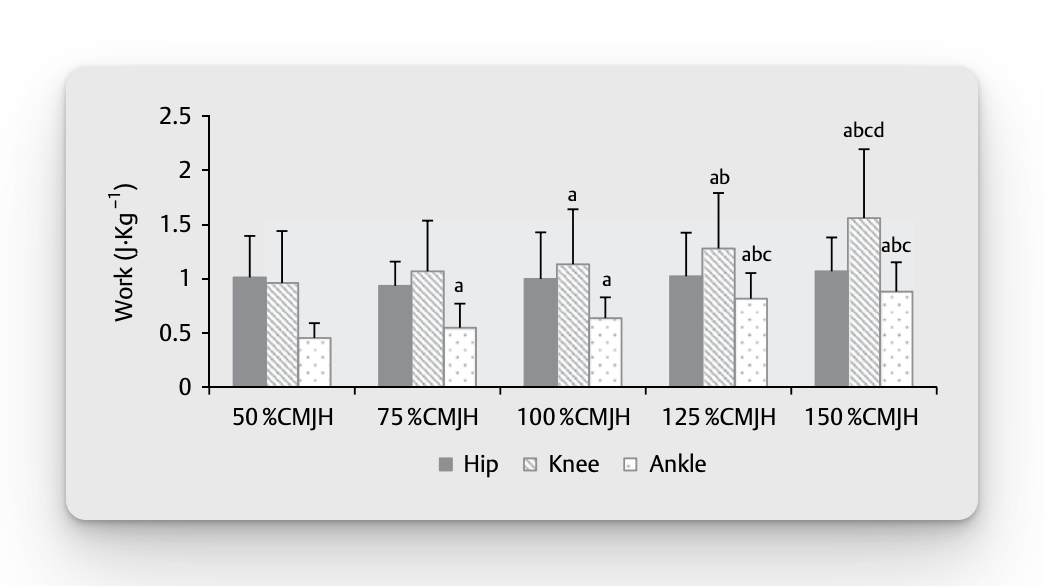

Knee and Ankle Took the Hit

Negative work at the knee and ankle increased substantially at 125% CMJ and 150% CMJ. Hip work stayed relatively stable. This suggests that, as height increases, the distal joint overload pattern increases.

What Does This Mean?

Drop heights above 100% CMJ:

- Increase braking demands

- Increase joint loading

- Do not improve jump output

The SSC appears to plateau, not amplify, at higher heights and the excess energy is likely dissipated as heat, not reused elastically.

In short, more drop height trains your ability to absorb force, not your ability to jump higher.

Limitations

- Male, elite volleyball players only

- Cross-sectional design (no training intervention)

Despite these limitations, the signal is clear for trained jump athletes.

Coach’s Takeaway

- Scale drop height to the athlete ⮕ Use each athlete’s CMJ to prescribe drop height rather than guessing box height.

- Stay in the 50–100% CMJ range for jump performance ⮕ This window maintains SSC efficiency while avoiding unnecessary joint loading.

- Drops above 100% CMJ bias attenuation, not utililization ⮕ Higher heights increase force absorption demands and may be useful for deceleration or tendon exposure (although we do not have great data here), but they do not improve jump height.

I hope this helps,

Ramsey

Reference

Peng, H-T., Song, C-Y., Wallace, B. J., Kernozek, T. W., Wang, M-H., & Wang, Y-H. (2019). Effects of relative drop heights of drop jump biomechanics in male volleyball players. International Journal of Sports Medicine.