Sprinting and acceleration are crucial in field sports like soccer, hurling, and rugby, where plays often hinge on short bursts of speed.

This study focused on understanding how reactive strength, the ability to transition rapidly from eccentric to concentric force, affects mid-to-late acceleration and sprint mechanics.

The researchers asked:

Does reactive strength (as measured by the 10/5 Repeated Jump Test) meaningfully contribute to sprint acceleration?

What Did the Researchers Do?

Researchers had 24 elite U21 male hurling players (avg. age: 19.2 yrs) perform jump and sprint test to determine their relationships.

Tests Used

- 10/5 Repeated Jump Test (RJT) to assess Reactive Strength Index (RSI).

- 3 x 30 m sprints with split times at 5, 10, 20, and 30 m.

Variables Measured

- RSI, Jump Height, Jump Contact Time (CTJUMP).

- Sprint segment times (0–5 m, 5–10 m, etc.).

- Step length, step frequency, ground contact time (CTSPRINT), and flight time using Optojump.

Pearson correlations were analyzed across acceleration phases and step kinematics.

What Were the Results?

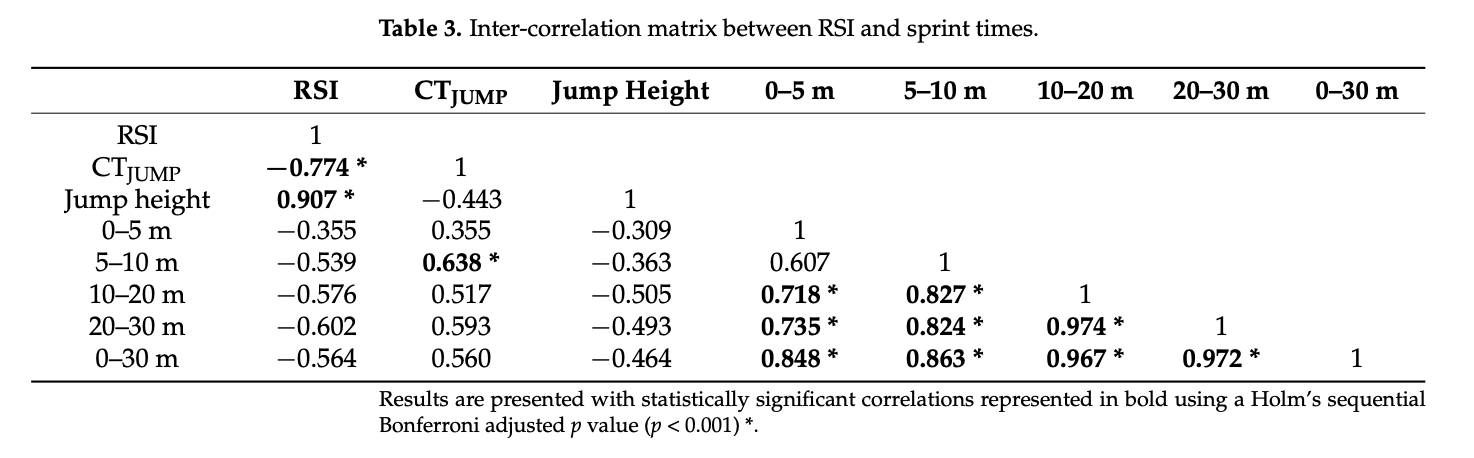

- Strong correlations between RSI and sprint performance from 5–30 m, particularly:

- 5–10 m: r = −0.539

- 10–20 m: r = −0.576

- 20–30 m: r = −0.602

- No significant correlation between RSI and the initial 0–5 m sprint segment.

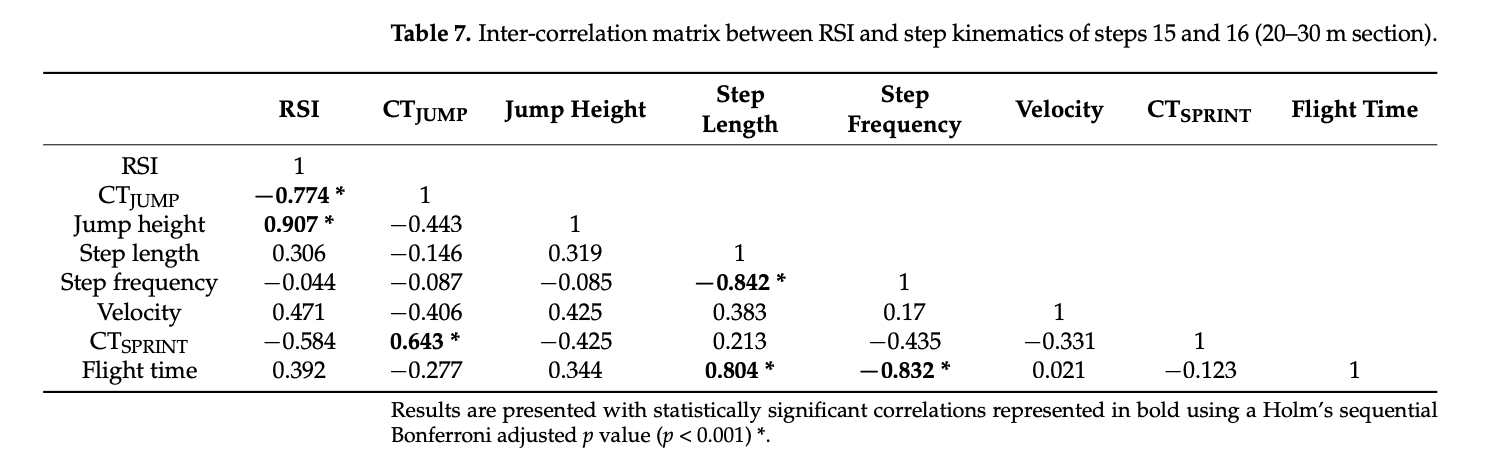

- RSI was strongly negatively correlated with CTSPRINT (i.e., better RSI = shorter ground contact).

- RSI did not significantly affect step length or frequency.

What Does This Mean?

- Reactive strength is more important in later sprint phases, where athletes must apply force quickly with shorter ground contact times.

- The mechanical link: RSI helps reduce CTSPRINT without compromising stride length or frequency.

- Early acceleration (0–5 m) may rely more on maximal strength or concentric capabilities than reactive qualities.

"An important and novel finding of this study is the identification of a potential mechanism by which reactive strength may positively influence sprint performance. The correlation between CTSPRINT and CTJUMP strengthens throughout the sprint phases from a moderate relationship in the early phases to a large significant relationship in the analysis

of steps 15 and 16 (within the 20–30 m sprint distance)."

Limitations

- Bilateral RJT may not reflect the unilateral, horizontal force demands of early sprinting.

- Limited to U21 hurling athletes; may not generalize to elite sprinters or other populations.

Coach’s Takeaway

- Train reactive strength (e.g., repeated jumps, drop jumps, ankle-specific plyos) to enhance late-phase sprinting.

- For early acceleration, prioritize maximal strength and horizontal force development (e.g., sled sprints, resisted starts).

- Use contact time metrics to track adaptations and monitor athletes with lower RSI values (<1.4).

I hope this helps,

Ramsey

Reference

Flanagan, E.P., Comyns, T.M., Harrison, A.J., & Brady, C.J. (2025). Reactive Strength Ability Is Associated with Late-Phase Sprint Acceleration and Ground Contact Time in Field Sport Athletes. Applied Sciences, 15(6910).