If you coach long enough, you hear a lot about “tendon stiffness,” “elasticity,” and “springiness” being the magic behind great jumpers.

Those qualities matter, but a 2021 study from McBride and colleagues cut straight to the truth:

In a true max-effort hop, the biggest difference between high and low performers is the amount of concentric muscle work they can produce.

This study put that idea to the test by isolating the ankle joint and measuring how much work came from the muscles vs the tendon.

How They Tested It

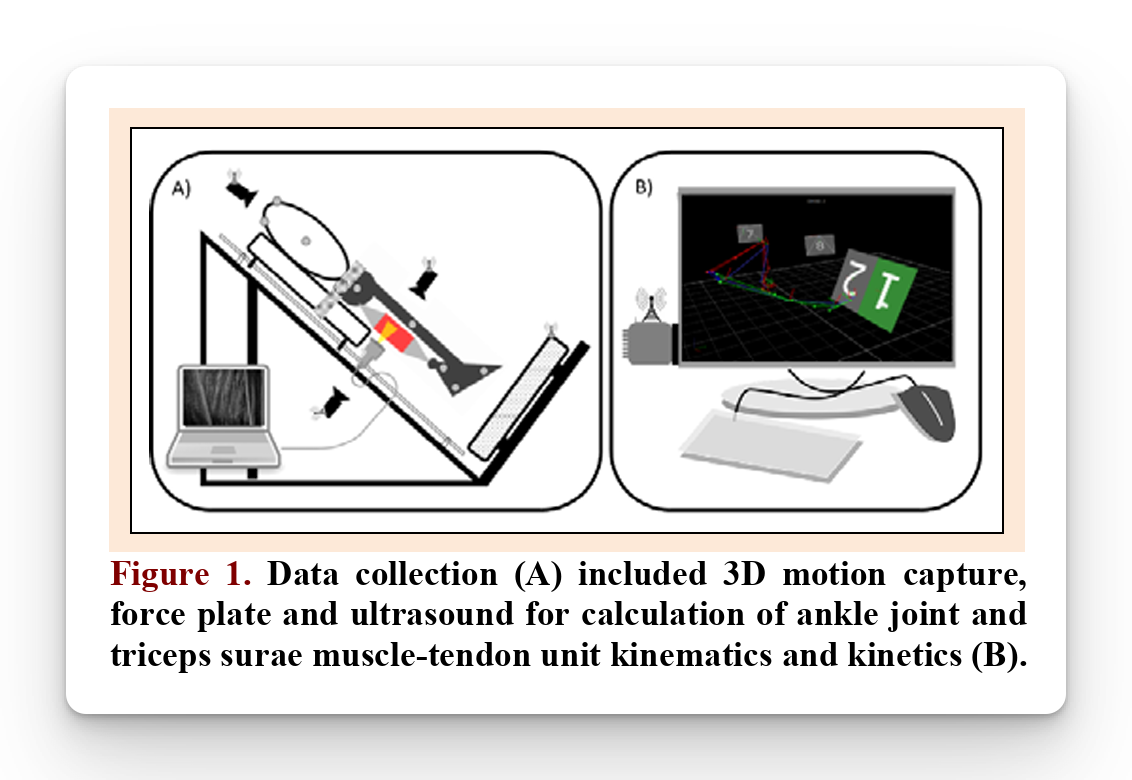

Researchers had athletes perform single-leg countermovement hops and drop hops (10 cm and 50 cm) on a 20 degree sled with the knee fully locked.

That means the ankle and triceps surae (gastroc–soleus) were doing all the work.

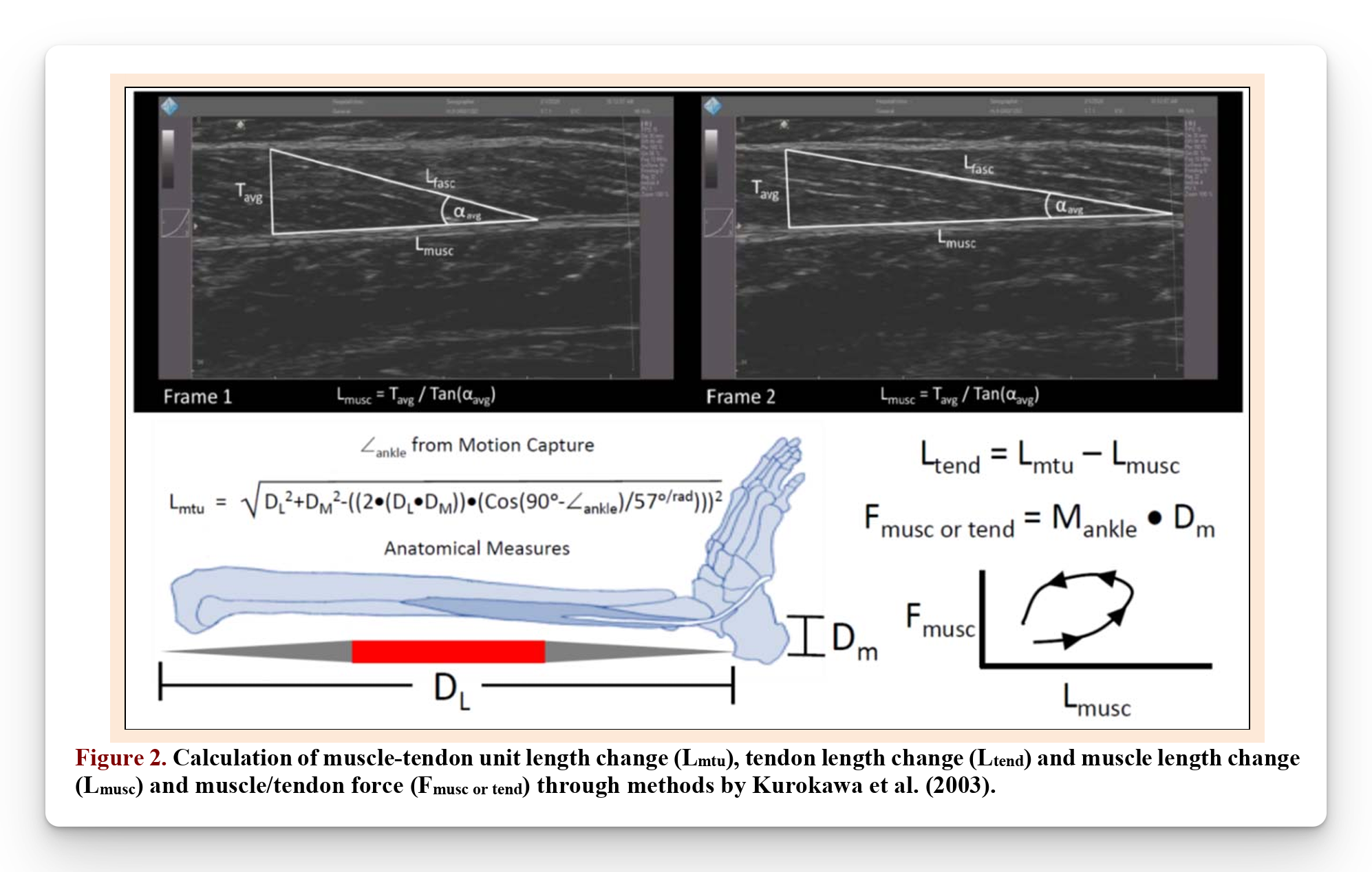

To understand what was actually driving hop performance, the researchers combined three measurement tools: motion capture, force plates, and ultrasound imaging of the triceps surae.

They captured:

- Active muscle work (fascicles actively shortening)

- Passive muscle work (elastic elements like titin)

- Tendon work (Achilles stretch and recoil)

- Hop height

Then they split participants into:

- Higher Hoppers (HH; ≥ 0.10 m hop height)

- Lower Hoppers (LH; < 0.10 m hop height)

This let them see exactly what separated the best performers.

What the Study Found (In Simple Terms)

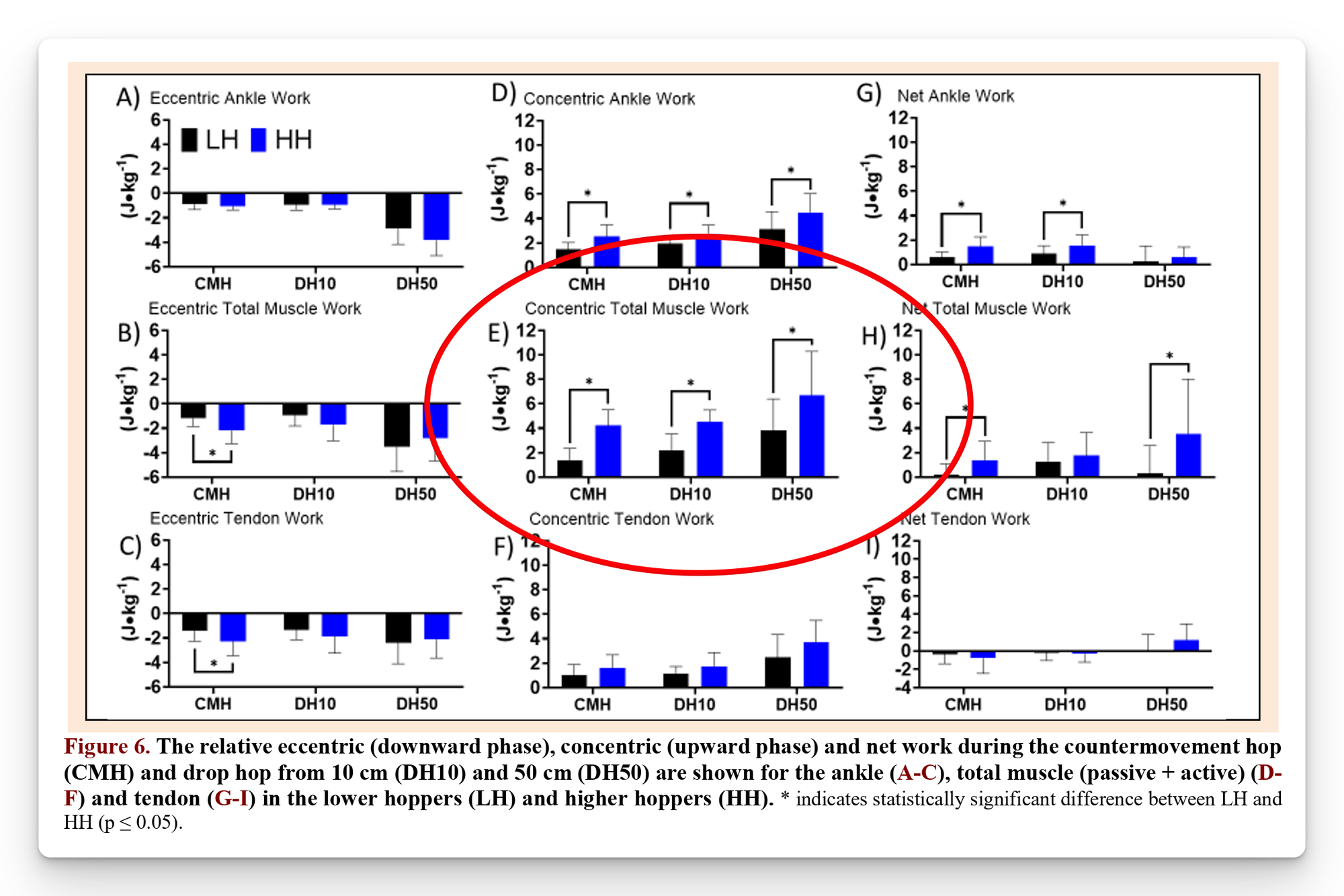

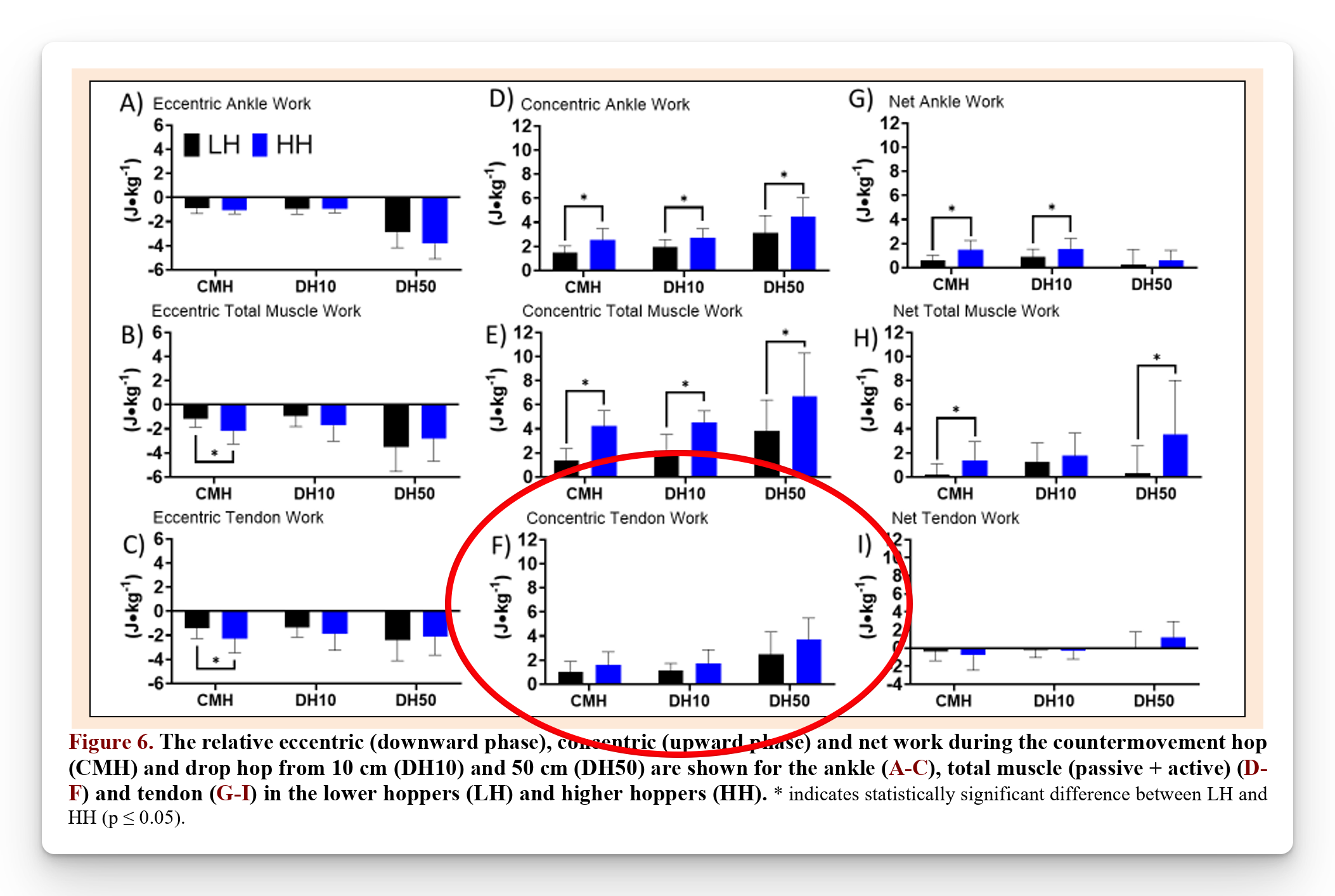

The big difference is concentric muscle work. Figure 6E shows it perfectly. Across all hop types:

- HH produced far more concentric muscle work than LH

- The separation is large and consistent

- Every condition showed a statistically significant difference

This is the clearest “blue vs black bar” gap in the entire figure.

Tendon work barely differed between groups.

Look at Figure 6F. Both groups’ tendon work bars look nearly the same. No meaningful gap. No real separation.

This alone kills the idea that elite performance in this task is primarily tendon-driven.

Active muscle work explains almost all of the performance differences.

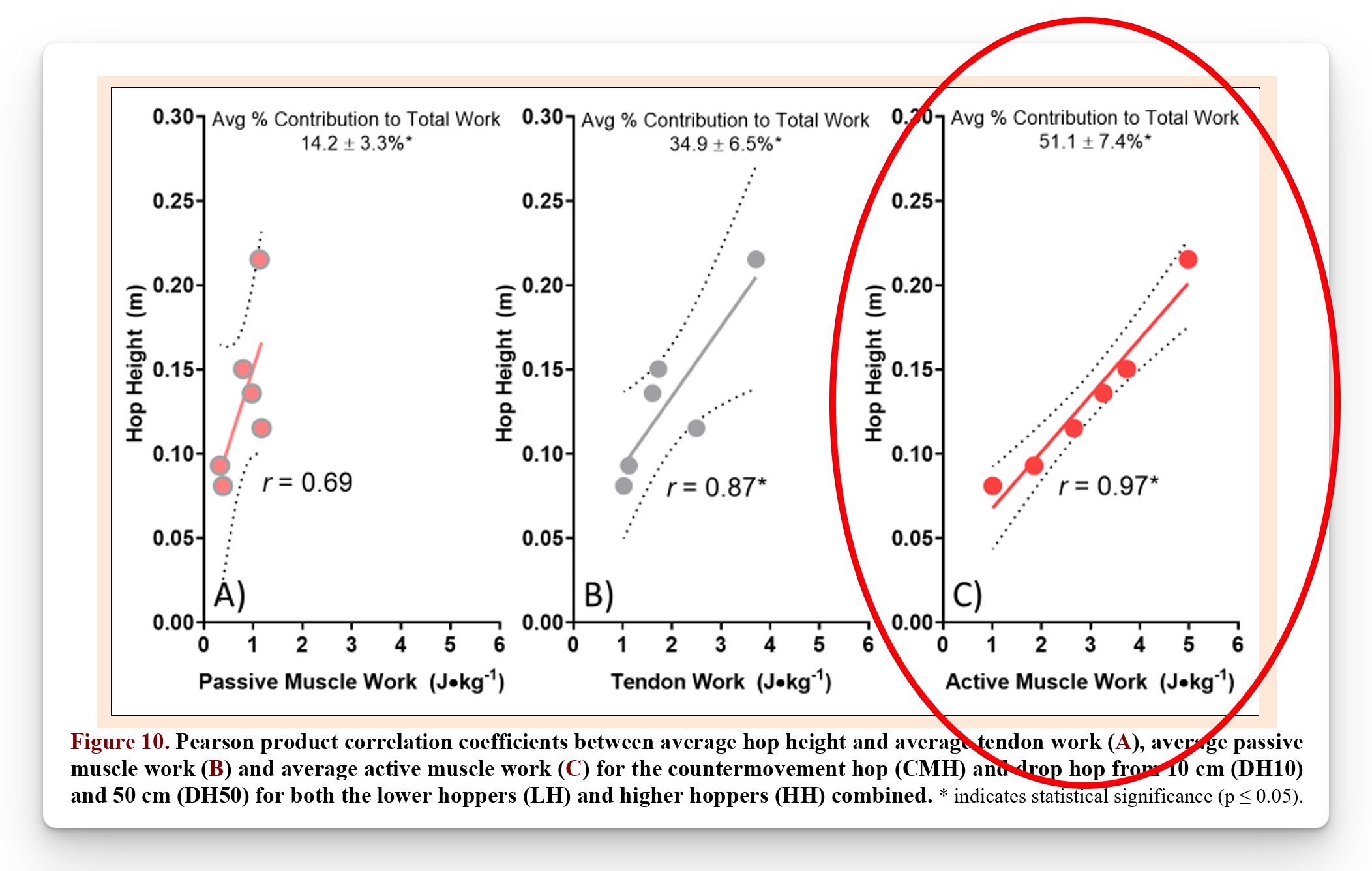

Figure 10 drives the point home:

- Active muscle work vs hop height: r = 0.97

- Tendon work vs hop height: r = 0.87

- Passive muscle work: basically irrelevant

When you see a correlation that strong, you are looking at the true engine of performance.

Higher hoppers weren’t more “elastic.” They were stronger.

Higher performers also had higher max isometric plantarflexion force. Stronger calves meant more ability to generate concentric muscle work.

That’s why they jumped higher.

What This Means for Coaches

Strength at the ankle is non-negotiable

- Higher jumpers separated themselves through concentric muscle work

- Prioritize heavy plantarflexion strength work, isometrics, and high-force calf training

Tendon training helps, but it is not the separator

- Tendon work barely differed between high and low performers in this study

- Use tendon-focused drills to support strength, not replace it

Build muscle work capacity before layering elasticity

- Athletes need muscular horsepower first

- Without strong plantarflexors, there is limited elastic energy to recycle

Single-leg ankle power transfers directly to sport

- Jumping, sprinting, braking, and cutting all rely on strong ankle contributions

- Training isolated ankle power carries over to sport-specific explosiveness

Coach's Takeaway

The authors state it clearly:

In conclusion, humans clearly use a predominance of active muscle contractility to enhance a single maximal effort performance. Active muscle work made up the largest component of the total work and correlated the highest with the resulting performance.

If your goal is to improve jumping and sprinting performance, this study gives you a clear north star.

Tendon doesn’t separate good from great. Muscle does.

Higher performers simply produce more concentric muscle work, and that is what lifts them off the ground.

Build strong calves, build powerful ankles, and your athletes will jump higher, sprint better, and move with more force in every direction.

I hope this helps,

Ramsey

Reference: McBride, J. M. (2021). Muscle actuators, not springs, drive maximal effort human locomotor performance. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 20(4), 766–777.