The Other-20™️

We obsess over the 3-4 hours athletes train each day, yet the other 20 hours throughout the day may be more influential than we realize.

A recent qualitative study on elite athletes shows that off-sport life is not neutral. It either supports performance or quietly interferes with it through a concept called spillover.

Data from the NBA shows that late-night social media activity (tweeting), used as a proxy for insufficient or delayed sleep, is associated with small but meaningful decrements in next-day game performance, particularly shooting accuracy. This reinforces that off-sport behaviors can spillover into sport performance.

Let's break down:

- What spillover actually is

- The types of off-sport activities elite athletes do

- When those activities help performance

- When they hurt it

- How coaches can apply this without overstepping boundaries

What Is Spillover?

Spillover is when emotions, thoughts, energy, and behaviors from one part of life carry into another.

In sport, that means:

- Stress from school or work shows up in training

- Confidence from progress outside sport carries into competition

- Boredom or rumination off-sport shows up as low energy or poor focus

Spillover can be positive (enrichment) or negative (interference).

The Off-Sport Categories

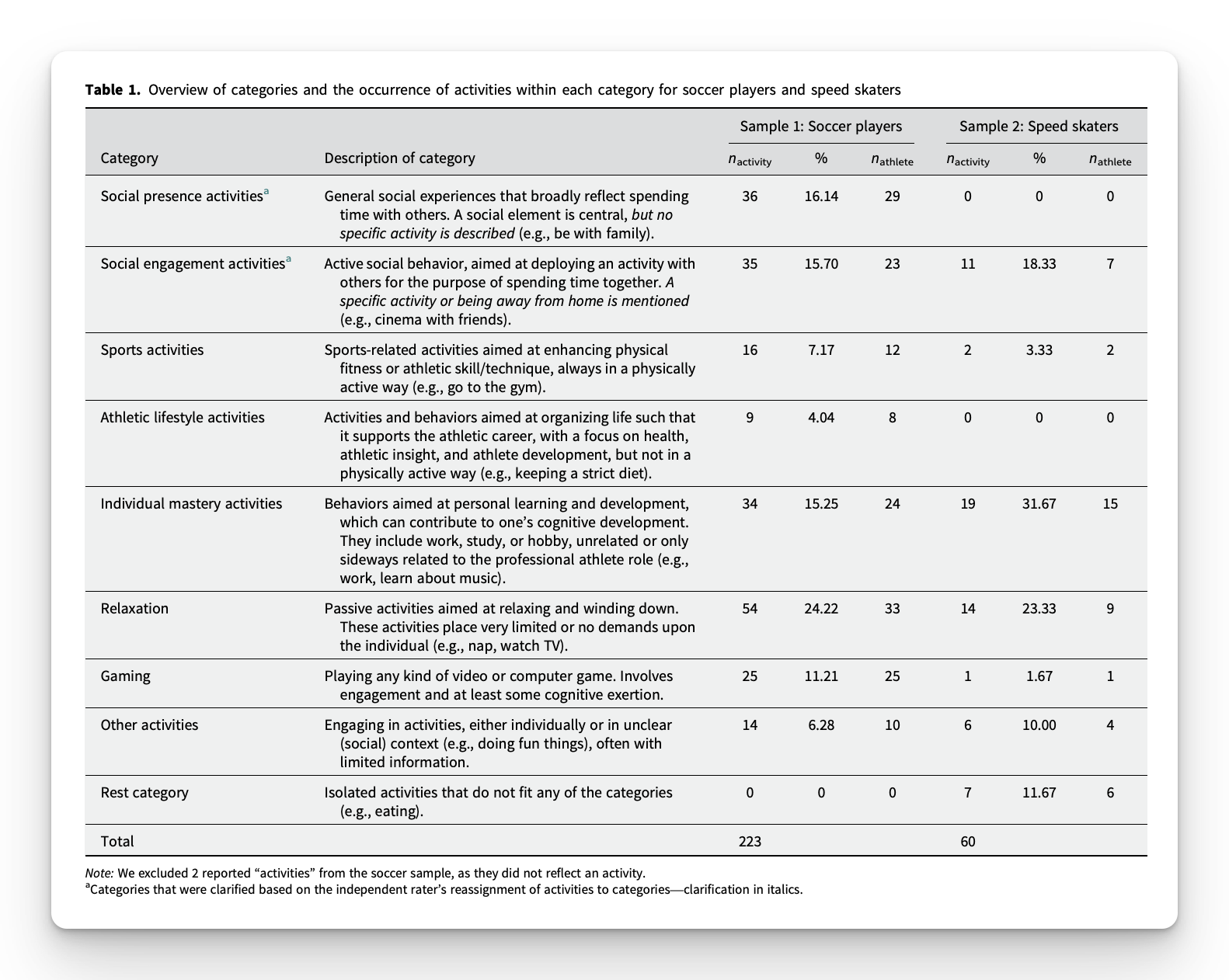

The researchers grouped off-sport activities into eight practical categories:

- Social Presence ⮕ Being around family or friends without a specific activity (e.g. hanging out, sitting together, shared time)

- Social Engagement ⮕ Actively doing something with others (e.g. meals, games, shared hobbies, outings)

- Sports Activities ⮕ Extra physical or sport-related work outside formal training (e.g. gym sessions, light skills work, individual movement)

- Athletic Lifestyle Activities ⮕ Behaviors that indirectly support sport performance (e.g. meal prep, recovery work, film study, mobility)

- Individual Mastery Activities ⮕ Goal-directed activities outside sport that involve learning or progress (e.g. studying, work, learning a skill, structured hobbies)

- Relaxation ⮕ Low-effort activities aimed at unwinding and downshifting (e.g. TV, naps, casual scrolling, listening to music)

- Gaming ⮕ Treated as its own category due to different cognitive and emotional demands

- Other ⮕ Activities that did not clearly fit into the categories above

Not all rest is passive, and not all activity creates fatigue.

Helpful Off-Sport Activities

Two mechanisms showed up repeatedly.

Mental Detachment

Athletes performed better when off-sport activities helped them mentally step away from sport.

This included:

- Studying

- Learning something unrelated

- Engaging hobbies

- Meaningful social interaction

Detachment reduced:

- Rumination

- Pre-competition worry

- Mental fatigue

Counterintuitive takeaway: Doing something mentally engaging outside sport often helped more than passive rest.

Confidence Transfer

Progress outside sport boosted general confidence, which carried into training and competition.

Examples athletes gave:

- Doing well on an exam

- Making progress at work

- Getting better at a skill unrelated to sport

This confidence was not technical or tactical. It was broader:

“I can handle challenges.”

That mindset transferred directly into sport.

Hurtful Off-Sport Activities

The study identified two very common traps.

Trap 1: Too Much Doing

Too many high-effort off-sport demands led to:

- Mental fatigue

- Poor sleep

- Stress

- Reduced readiness in training

Examples:

- Heavy academic load with no flexibility

- Work demands stacked on top of full training

- Constant productivity with no downshift

This is overload, not balance.

Trap 2: Too Much Nothing

Surprisingly, excessive passive downtime also caused problems.

Athletes described:

- Boredom

- Rumination about sport

- Overthinking mistakes

- Feeling flat or lazy in training

Not all “chill time” leads to recovery if it lacks structure or meaning.

What Determines Whether Spillover Is Positive or Negative?

Five conditions mattered a lot.

- Autonomy ⮕ Athletes who could choose how and when they did off-sport activities managed load better.

- Flexibility and Support ⮕ Flexible schools, understanding coaches, and supportive organizations reduced interference.

- Social Environment ⮕ Supportive teammates helped normalize balance.

- Intrinsic Motivation ⮕ Activities chosen because the athlete wanted them worked better than forced ones.

- Clear Priorities ⮕ Athletes who knew what mattered in-season vs off-season navigated tradeoffs better.

Rigid systems increased negative spillover even when intentions were good.

What This Means for Strength & Conditioning Coaches

Stop Treating Off-Sport Life as “None of Your Business”

You do not need to micromanage athletes’ lives. But ignoring off-sport behavior means missing a major performance variable. This is not about control. It is about awareness.

Think in Balance, Not Extremes

Performance did best when athletes had:

- Some active, engaging off-sport time (mastery, social engagement)

- Some true downshift time (sleep, relaxation)

Too much of either created problems.

Build a Simple “Life Recovery Menu”

Instead of telling athletes to “recover better,” offer structure. For example, each week, encourage athletes to identify:

- One activity that helps them mentally detach

- One activity that helps them genuinely relax

Let them choose.

Protect Flexibility Where You Can

Small changes matter:

- Flexible training plans

- Understanding academic load

- Adjusting non-essential demands during congested weeks

The study was clear. Flexibility changed outcomes.

Think at the System Level

The authors even suggested physical spaces:

- Areas for learning or mastery

- Areas designed for calm and relaxation

The environment can shape behavior.

Coach's Takeaway

While this was a qualitative study with a small sample size, the patterns were consistent and practical.

Off-sport life is not background noise. It is either:

- Fuel for better training and performance, or

- A quiet drain that shows up as fatigue, stress, or low engagement

The goal is not to eliminate stress or maximize rest. The goal is intentional balance.

And that balance is absolutely something good coaches can help guide.

If you want to level up your coaching with science-backed, proven methods, join our next cohort of Applied Performance Coach.

I hope this helps,

Ramsey

References:

- Postema, L., van Mierlo, H., & Bakker, A. B. (2025). Elite athletes’ off-sports activities: A qualitative exploration of spillover to the sports domain. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 77, 102860.

- Jones, J. J., Kirschen, G. W., Kancharla, S., & Hale, L. (2019). Association between late-night tweeting and next-day game performance among professional basketball players. Sleep Health, 5(1), 68–71.