Deceleration is a limiting factor in high-level sport. Stopping fast, changing direction, and "absorbing" force safely all depend on how well an athlete manages eccentric load.

Drop landings are commonly used to screen landing mechanics, progress rehab and build eccentric capacity.

We overload landings in two main ways: Increasing drop height (velocity-dominant) or adding external load (mass-dominant)

Both increase impact momentum, but do they stress the system the same way?

This study examined how landing mechanics change when impact momentum is increased via height vs load.

Do height and load change forces, impulses, and landing strategies differently?

What Did the Researchers Do?

Participants

- 15 recreationally trained adults

- All could back squat at least bodyweight

- No current or prior injuries limiting landing ability

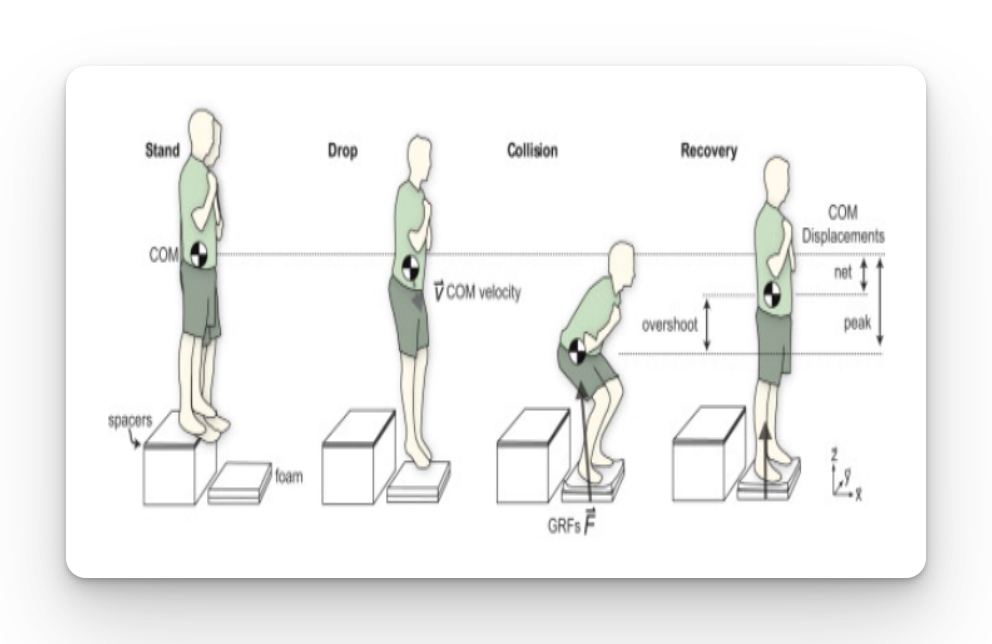

Participants performed bilateral drop landings under two conditions:

HEIGHT (velocity-dominant)

Bodyweight landings from:

- 0.60 m

- 0.91 m

- 1.22 m

LOAD (mass-dominant)

Fixed height (0.60 m), holding kettlebells:

- 16 kg

- 28 kg

- 40 kg

Each condition included four trials. The trial with the shallowest landing depth was used for analysis to reflect maximal stiffness strategies.

Key Variables Measured

- Average vertical ground reaction force (vGRF)

- Average eccentric velocity

- Landing depth

- Loading impulse (initial impact → peak vGRF)

- Attenuation impulse (peak vGRF → zero velocity)

What Were the Results?

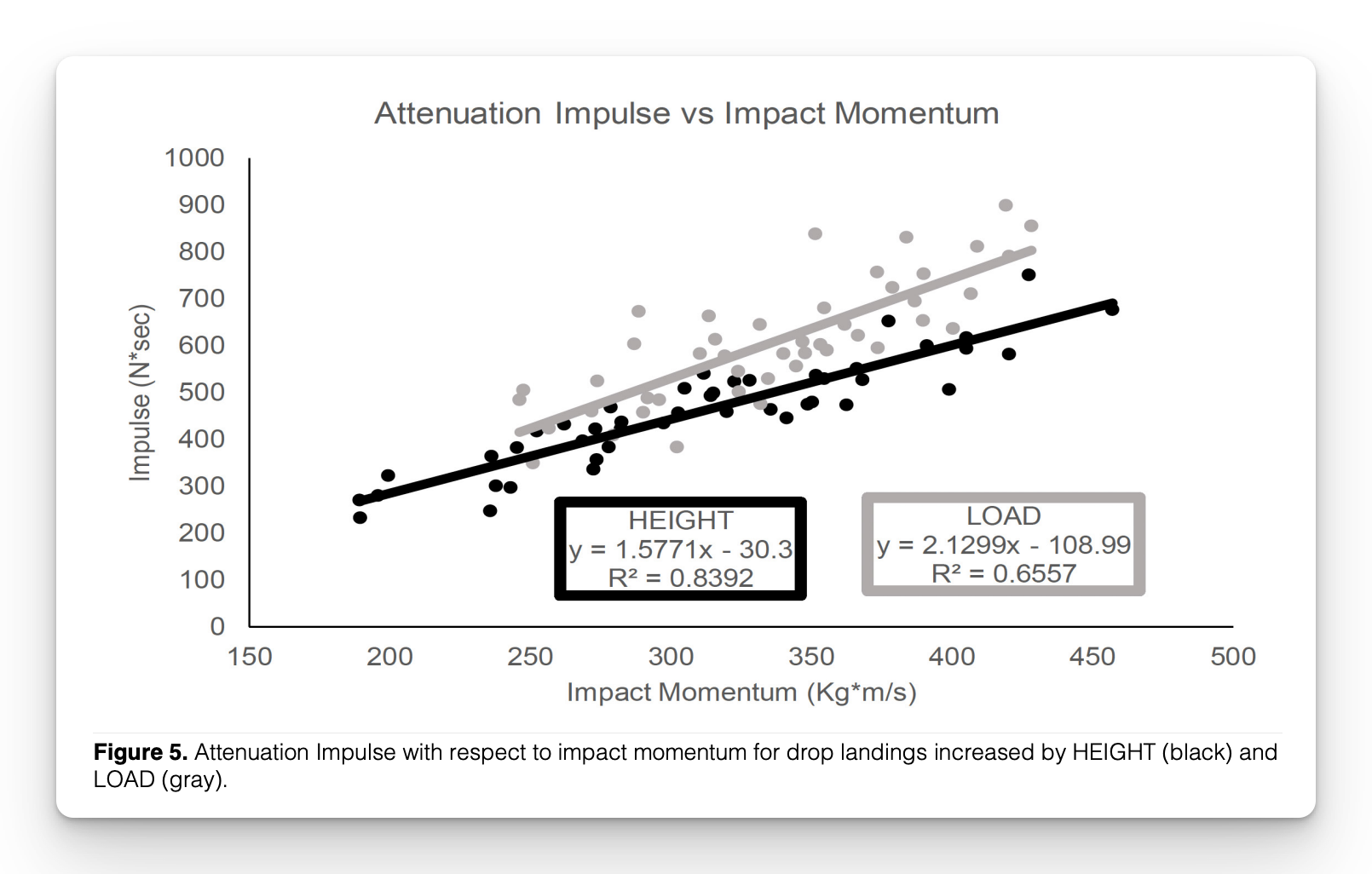

Attenuation Impulse Responds Strongly to Both Height and Load

- R² = 0.84 for HEIGHT

- R² = 0.66 for LOAD

As momentum increased, athletes consistently increased how much force they attenuated after peak impact, regardless of how that momentum was created.

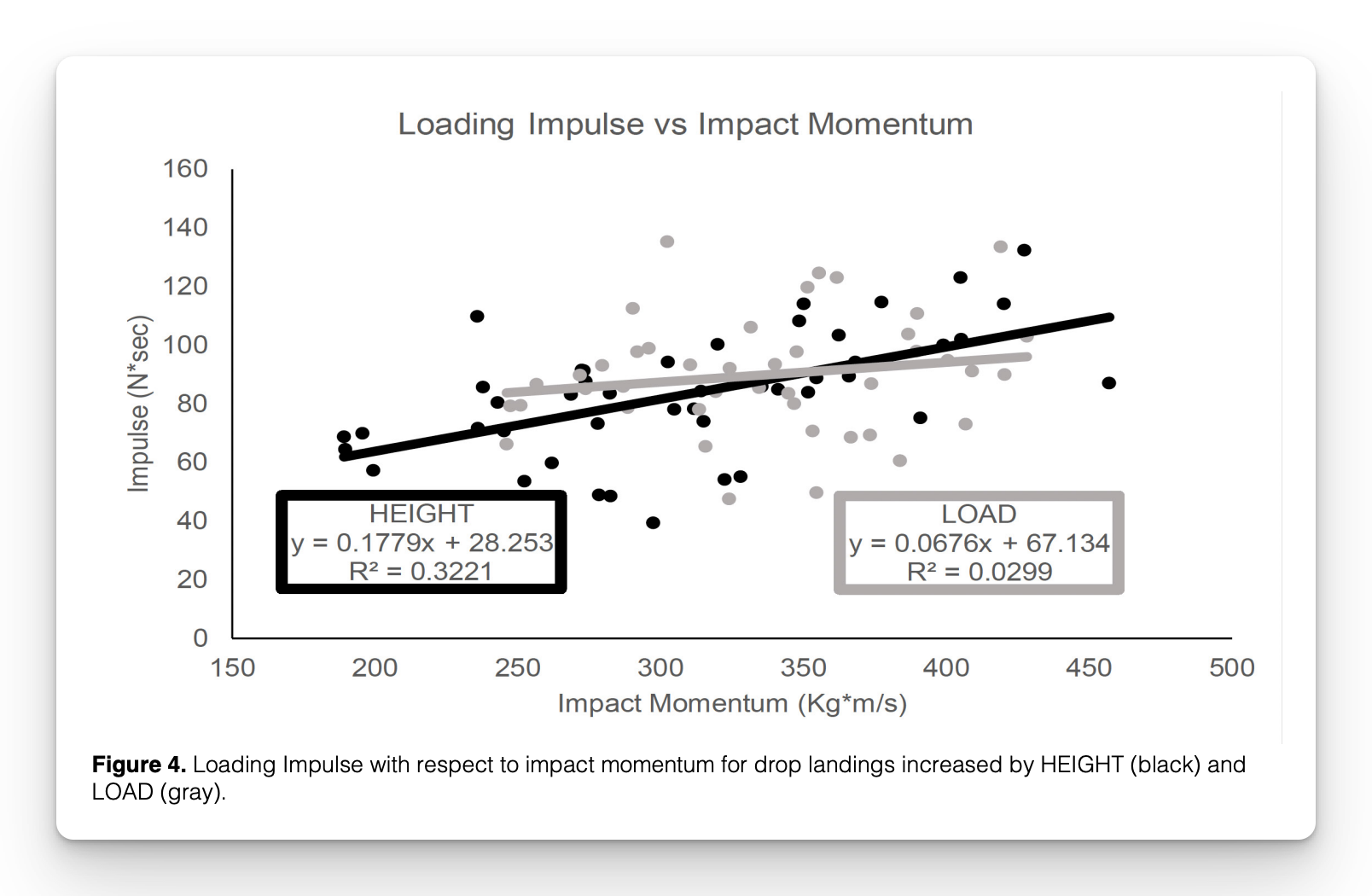

Loading Impulse Increased More With HEIGHT Than LOAD

- HEIGHT showed a moderate, significant increase

- LOAD showed no meaningful relationship

Higher drops increase early impact stress, whereas adding load does not necessarily spike initial impact forces.

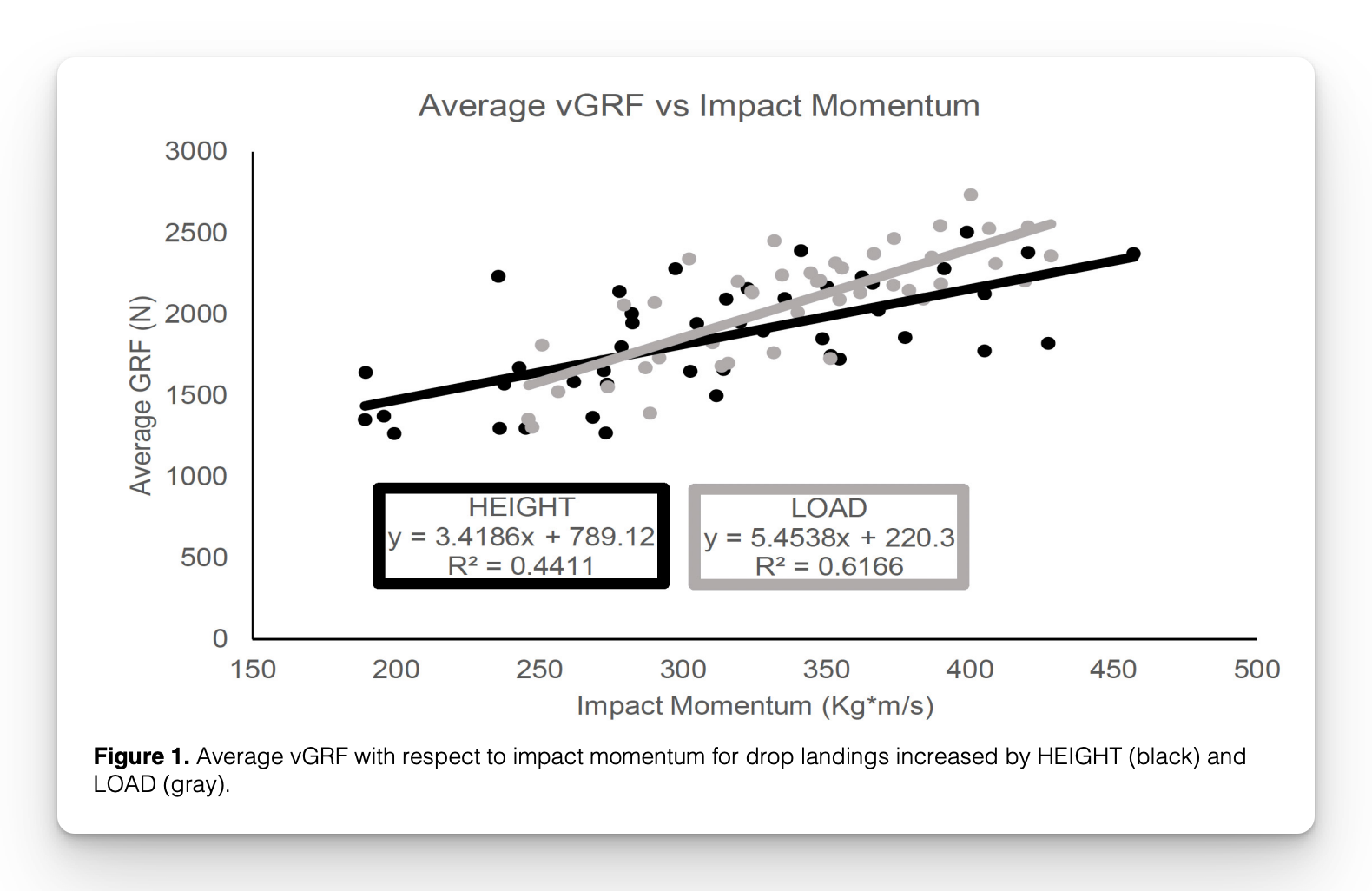

Average vGRF Increased More With LOAD

- LOAD had a stronger relationship with force than HEIGHT

This suggests heavier landings lead to higher average forces across the entire deceleration phase, not just the initial impact.

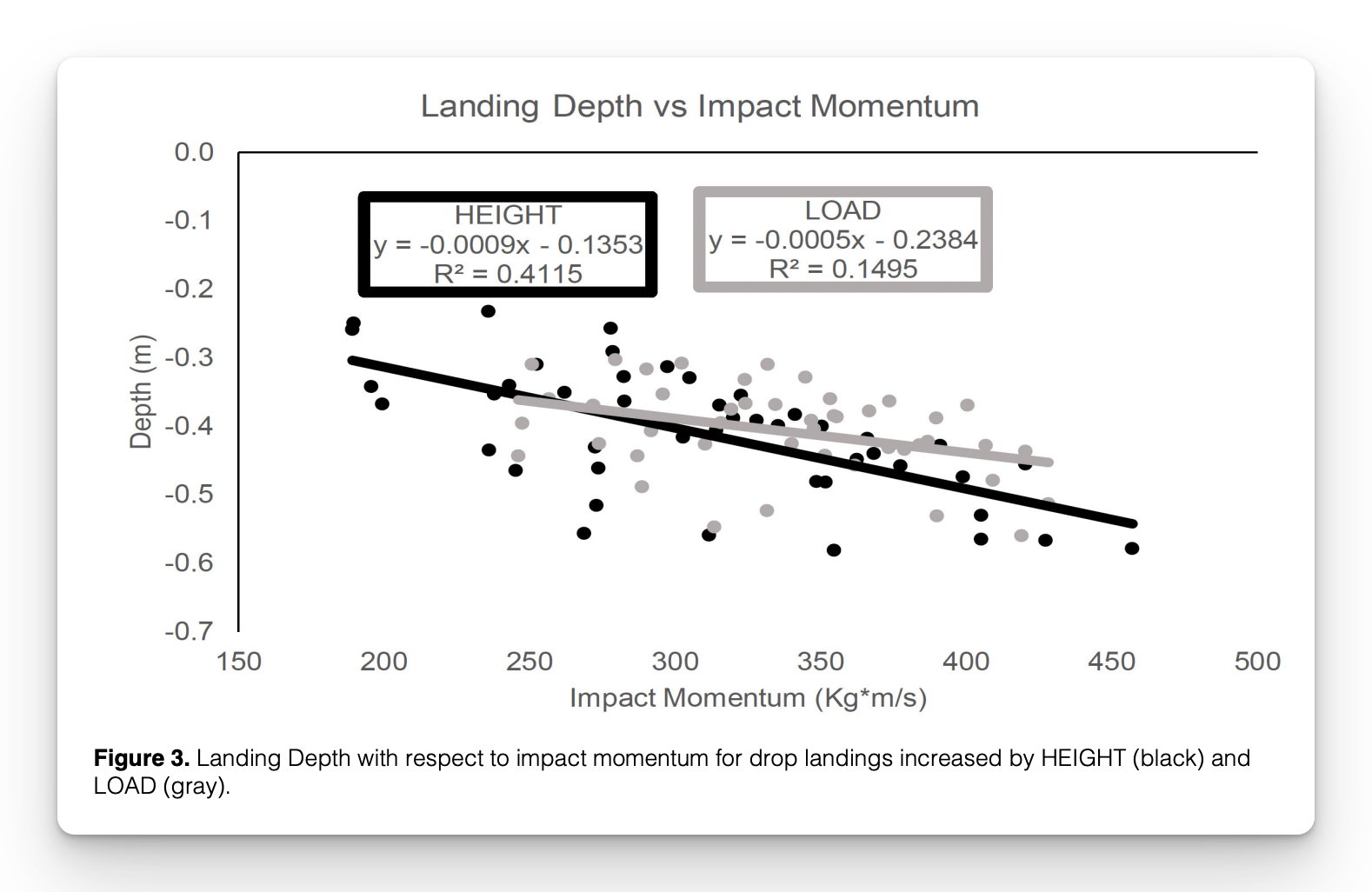

Landing Depth Increased More With HEIGHT

- Athletes sank deeper as drop height increased

- Landing depth changes were smaller and more variable with LOAD

Height encourages more joint excursion, while load allows stiffness to be preserved.

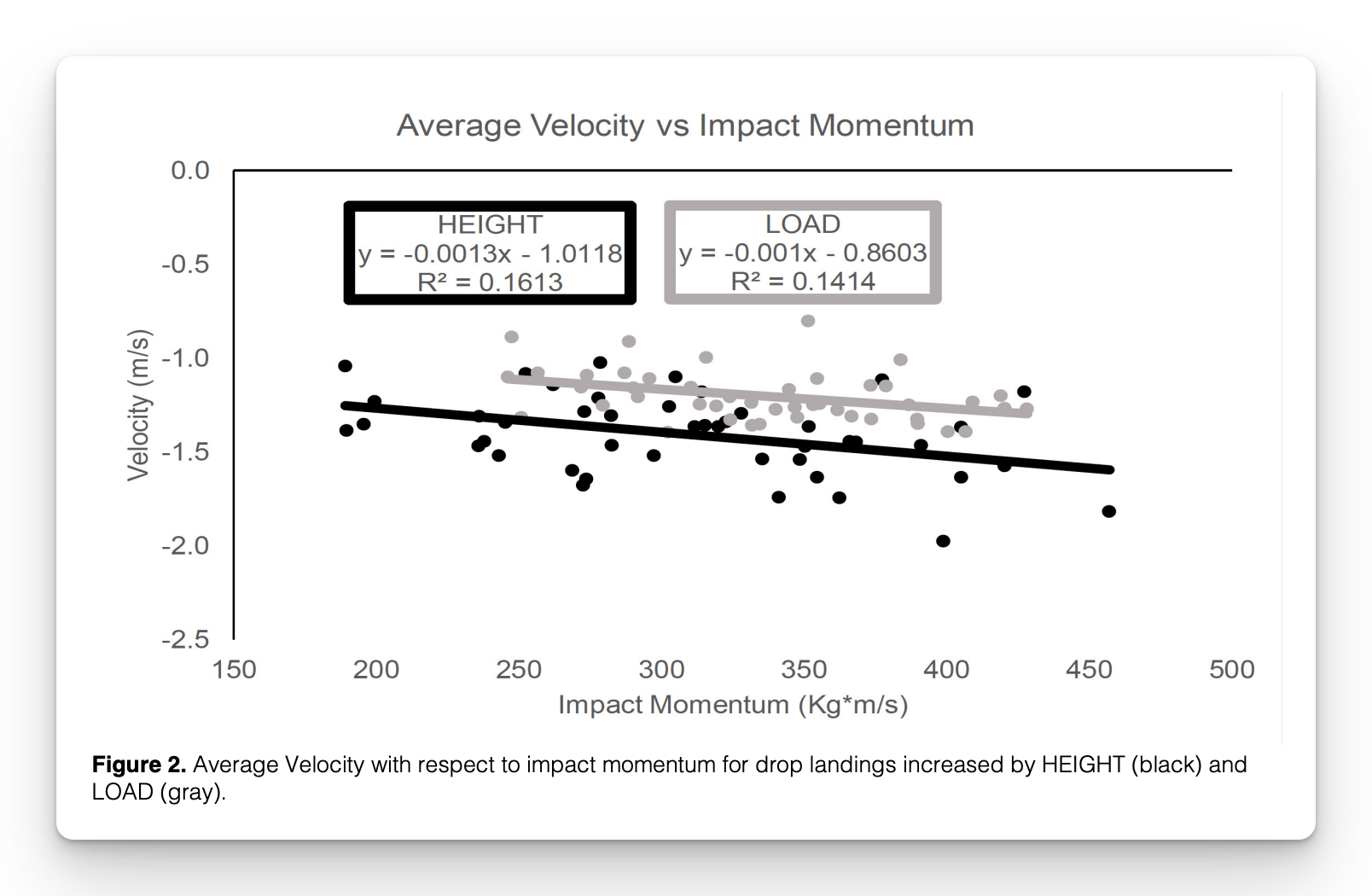

Average Eccentric Velocity Was Highly Variable

- Weak relationships across both conditions

- Significant individual differences

This reinforces that athletes self-organize deceleration strategies based on strength, tendon properties, and coordination.

What Does This Mean?

- Height and load both increase deceleration demand, but through different pathways.

- Height biases early loading, faster impact velocities, and deeper landings.

- Load biases force magnitude and attenuation, without large increases in loading impulse.

This matters because high loading impulse is linked to injury risk, while high attenuation impulse is linked to braking capacity and durability.

In short, how you overload matters just as much as how much.

Limitations

- Recreationally trained population

- Acute responses only, no long-term training effects

- No joint-level kinematics or kinetics

Coach’s Takeaway

- Height and load are not interchangeable tools for eccentric training.

- Use load to increase attenuation demands without spiking early impact stress.

- Use height when preparing athletes for fast SSC actions like sprinting and jumping.

I hope this helps,

Ramsey

Reference

Barker, L., Marcuzzo, L., Wright, N., Hulse, T., Patterson, C., Dishno, O., & Harry, J. (2026). Differences in Deceleration Mechanics from Mass- vs Velocity-Dominant Impact Momentum. International Journal of Strength and Conditioning.