Sprint performance matters across sports, but most team sports sprints are short, and athletes often never reach true max velocity (they live in acceleration).

Resisted sprints are a common method for increasing speed.

This new review examined whether athlete characteristics (age, sex, training level) and programming variables (frequency, volume, session count) affect outcomes of resisted sprint training.

I’ve summarized this review as succinctly as possible, but it’s a thorough, data-heavy paper. The main coaching takeaway is:

- Untrained or recreationally active athletes do not necessarily need resisted sprint training, as unresisted sprinting alone produces similar improvements.

- In contrast, trained athletes can benefit from resisted sprint training when using moderate loads (≥20–50% body mass or >10–30% velocity decrement) and very heavy loads (≥80% body mass or ≥50% velocity decrement), which provide a meaningful stimulus beyond normal sprinting.

What follows is a breakdown of the latest systematic review and meta-analysis on the effects of resisted sprint training.

When using sled sprints, how heavy should you load them, and what sprint phase does it actually improve?

What Did the Researchers Do?

Study Design

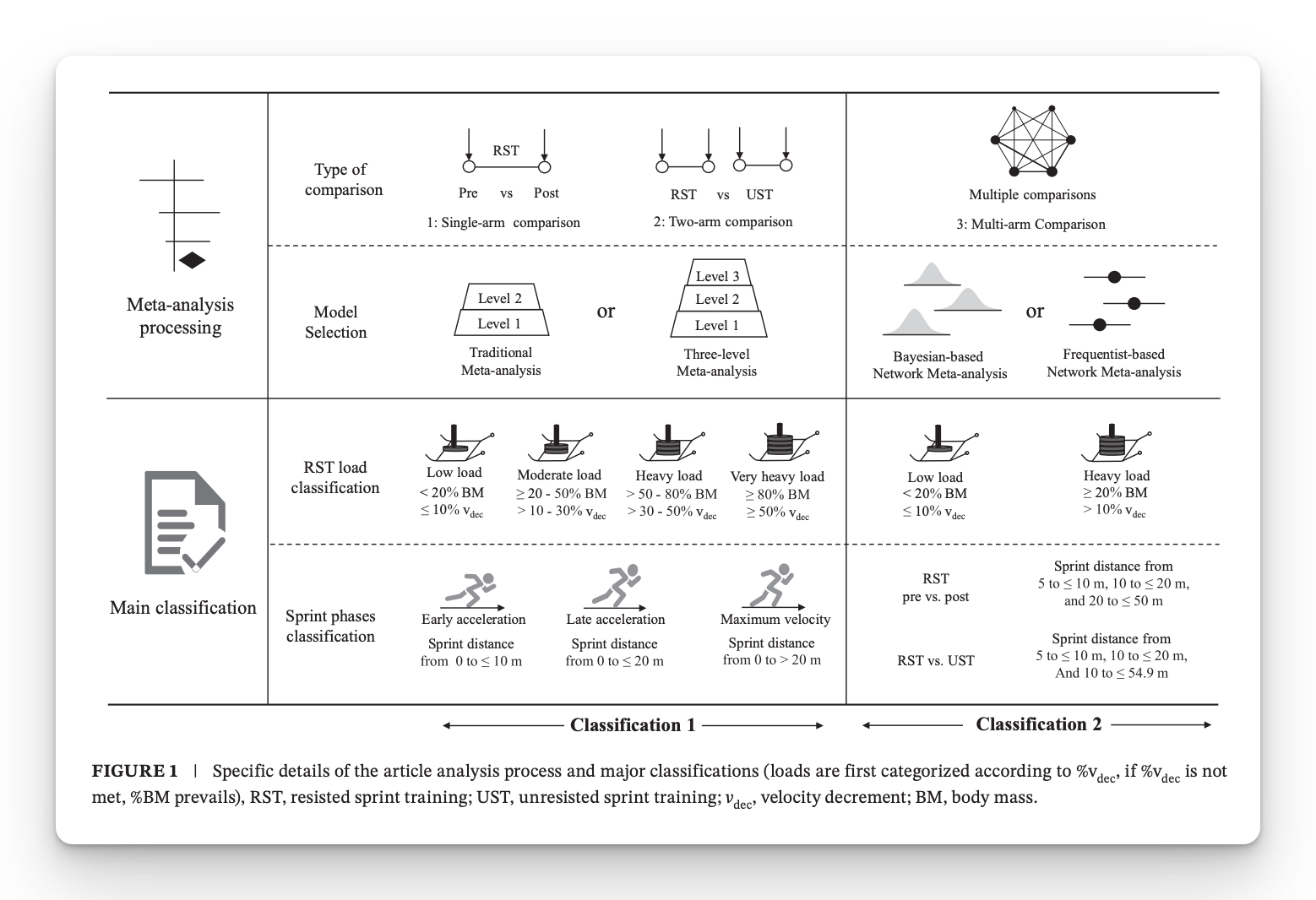

- Researchers conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis, including multiple analytical approaches.

- Included longitudinal interventions using horizontal resistance (mostly sled towing).

- 49 studies were included in the meta-analysis.

Participants

- Total sample of 1281 (mostly male), ages roughly 10–27 years.

- Mostly team sport athletes, with a small number of sprinters included.

Loads and Classifications

They categorized loads two ways, but the most useful is the 4-bin model:

- Low: <20% body mass (BM) or ≤10% velocity decrement (%vdec)

- Moderate: ≥20–80% BM or >10–30% vdec

- Heavy: >50–80% BM or >30–50% vdec

- Very heavy: ≥80% BM or ≥50% vdecEffects_of_Resisted-Sprint_Trai…

Sprint Phases

They also split sprint performance into phases and analyzed distance segments (like 0–5 m emphasis).

- Early Acceleration: 0 - <10m

- Late Acceleration: 0 - <20m

- Max Velocity: 0 - >20m**

Programming ranges observed across studies

- Single sprint reps: 5–55 m

- Session distance: 30–600 m

- Weekly distance: 60–1200 m

- Total distance: 380–6720 m

- Frequency: 1–3x/week, total sessions 6–36.

What were the results?

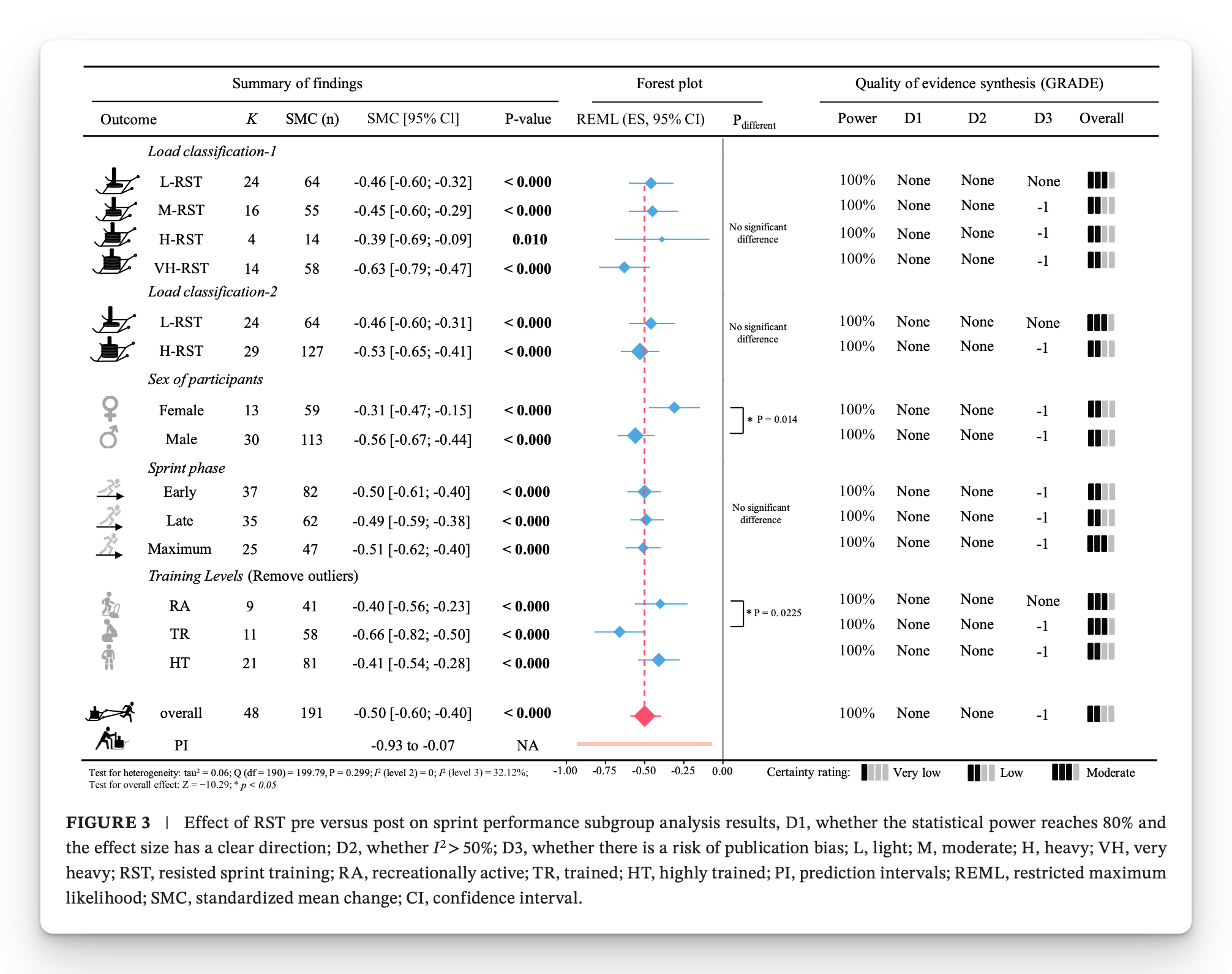

RST works, but load changes “where” it works.

- Very heavy loads consistently ranked as most effective in the network meta-analysis, outperforming UST, and beating light loads as well.

The most significant transfer shows up in early acceleration (especially 0–5 m).

- Most of the improvement attributed to very heavy loads appears driven by the early acceleration phase, and when early acceleration is excluded, effects are more modest and RST does not clearly outperform UST.

Improvements across distances exist, but the advantage over UST shrinks later.

- Across studies, sprint times improved in 5–10m, 10–20m, and 20–50m.

- But the authors emphasize that the benefits of RST over UST is strongest early, and not reliably superior later in the sprint.

Training level matters (big time).

- Recreationally active: light loads tend to be enough.

- Trained + highly trained: moderate and very heavy loads show bigger effects.

Mechanics shift in the “force direction” you care about.

- The paper ties the performance change to better early-acceleration mechanics, including improvements in variables like F0, Pmax, RFmax, especially with very heavy loads.

What Does This Mean?

Here’s the coaching translation:

- Very heavy sleds are a force-oriented stimulus ⮕ They are most useful when you want to bias adaptation toward the first steps (0–5 m).

- Light sleds are not useless ⮕ They often match UST and may be plenty for less trained athletes or those still cleaning up mechanics.

- Volume is not one-size-fits-all ⮕ Their meta-regression suggests heavier loads can get big results with fewer sessions and lower total distances, and that volume-response can look “inverted U-shaped” for moderate and very heavy loads (too little is not enough, too much may wash out quality).

Limitations

- Certainty is not high, as the researchers downgraded evidence frequently due to risk-of-bias, imprecision, and heterogeneity.

- Many studies are team sport athletes, not pure sprinters, and testing devices varied (timing gates, radar, stopwatch in some).

- Load reporting differs (%BM vs %vdec); the researchers used conversions, which is practical, but it’s still an extra layer of assumptions.

Coach’s Takeaway

Sprint Phase Prescriptions

- If your need is first-step dominance, heavy sleds make sense.

- If you’re chasing later acceleration or upright speed, you still need upright sprint exposure.

Trained Athletes Prescription

- Load: Use very heavy RST (≥80% BM or ≥50% vdec)

- Sprint distance per rep: 7.5–30 m

- Session volume: 45–135 m

- Duration: At least 4 weeks

- Total intervention volume: 800–1440 m

I hope this helps,

Ramsey

Reference: Xu K, Jukic I, Cross MR, Hicks DS, Yin MY, Zhong YM, Tang WJ, Li YF, Liang ZD, Wang R, Morin J-B, Girard O. (2025). Effects of Resisted-Sprint Training on Sprint Performance and Mechanics: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Focusing on Load Magnitude. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports.