Change of direction (COD) movements are central to basketball performance, especially during high-speed drives, defensive recoveries, and 180° cuts.

Understanding which aspects of COD (acceleration, braking, or re-acceleration) most influence performance helps coaches design targeted training.

This study examined NCAA Power 4 male basketball players using a modified 505 test to break down COD performance into specific mechanical phases.

The goal was to identify which variables best explained total COD time and whether there were positional differences between guards and bigs.

When an athlete changes direction, which specific parts of that movement most determine how fast they complete the turn, and do guards and bigs rely on different strengths?

I am developing the ultimate basketball performance course and certification program. This is a practical, no-fluff system for training basketball players, from the weight room to game day, and everything in between.

What Did the Researchers Do?

Researchers had 124 NCAA Division I Power 4 male athletes (70 guards, 54 bigs), perform a COD test during preseason.

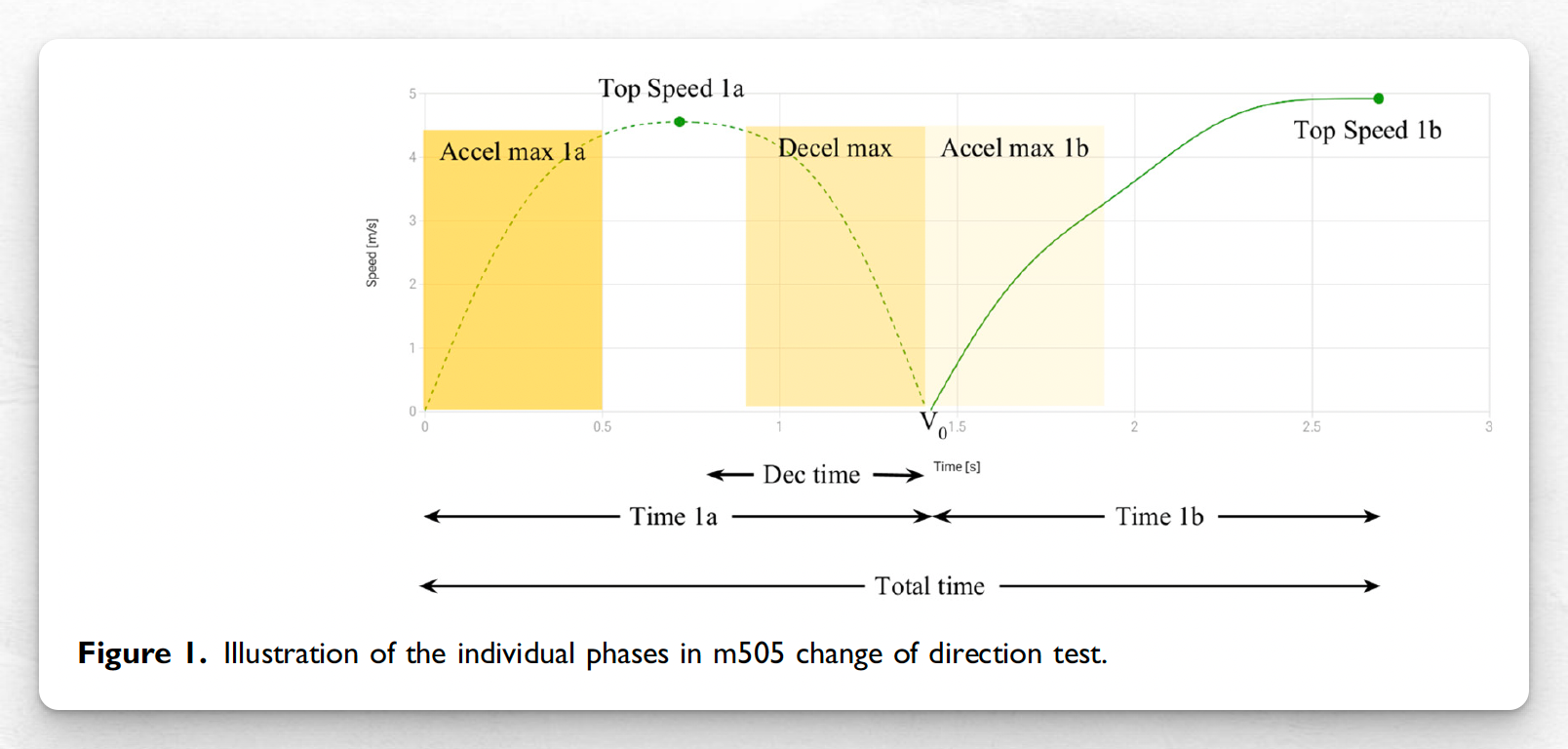

Modified 505 COD Test

- A modified 505 test using a 1080 Sprint motorized resistance device with a constant 3 kg load.

- Each athlete completed a 5 m approach, 180° turn, and 5 m return.

- Data were collected at 333 Hz and filtered using a fourth-order Butterworth filter; both left and right turns were analyzed.

Phases and Variables:

- Phase 1a: Approach phase from start to velocity zero at the turn.

- Phase 1b: Exit phase from velocity zero back to the start line.

- Key variables included time for each phase, top speed, maximum acceleration in each phase, and maximum deceleration.

- Multiple linear regression was used to determine which variables predicted total COD time, and t-tests compared guards and bigs.

What Were the Results?

Overall Performance

- The average total time for the m505 test was 3.18–3.27 seconds.

Key Predictors

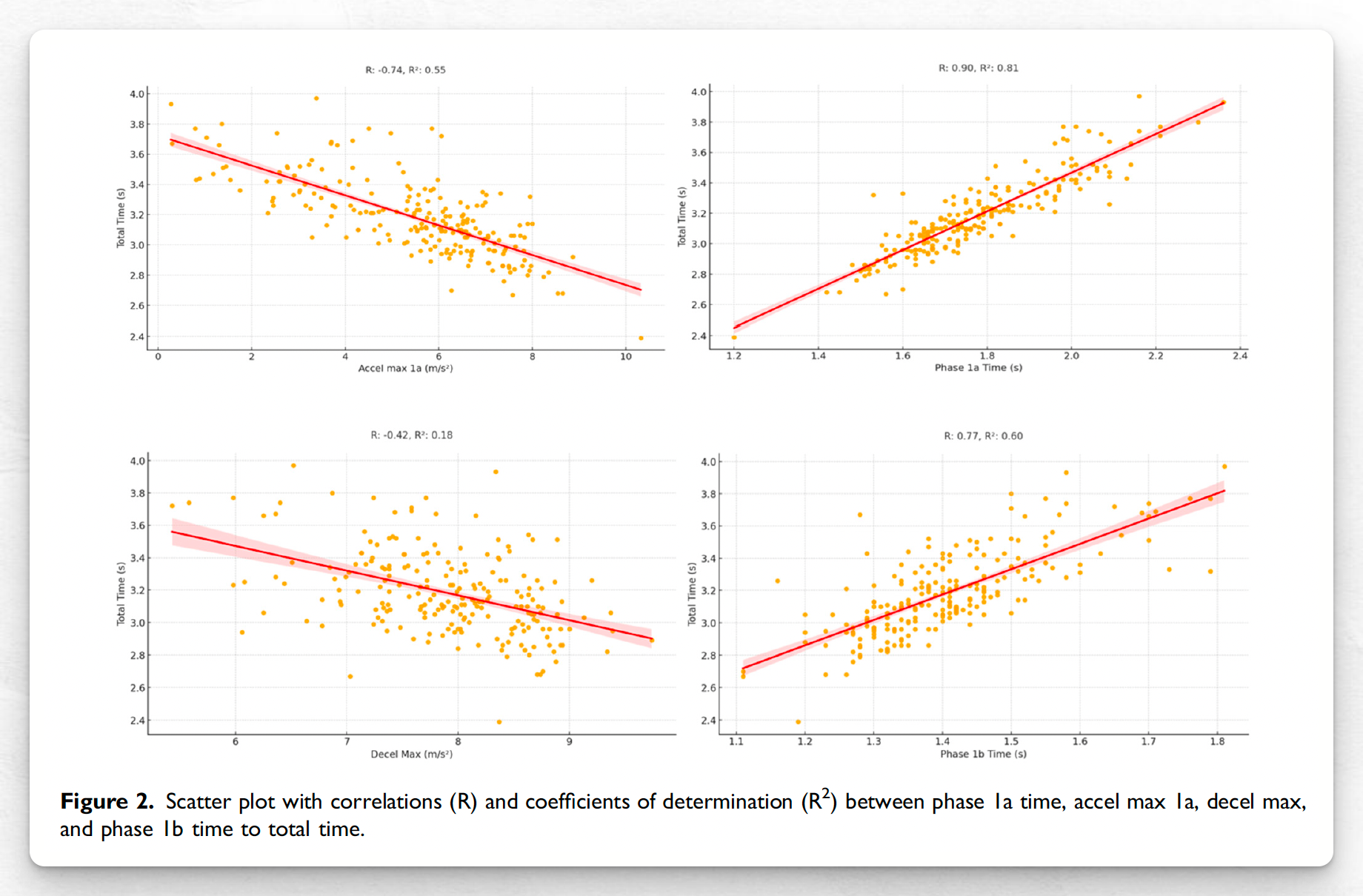

- Faster Phase 1a time and Phase 1b time were both associated with faster total times.

- Higher Acceleration Max 1a and Deceleration Max also predicted faster total times.

- Top Speed 1b and Acceleration Max 1b were not significant predictors.

Position Differences

- Guards showed higher Top Speed 1a and Deceleration Max on both legs compared to bigs.

- Guards also had slightly shorter deceleration times.

- Total times were similar between positions; differences were found in how they achieved those times.

What Does This Mean?

- The early approach matters most ⮕ Athletes who accelerate quickly into the turn (Phase 1a) and can brake more forcefully and efficiently before the plant complete the COD faster overall.

- Deceleration quality is critical ⮕ Maximum braking force was a key differentiator, reinforcing the importance of eccentric control and braking mechanics in COD ability.

- Top-end exit speed isn’t the main driver ⮕ The ability to reach a high but controllable approach speed and manage braking appears more influential than simply how fast athletes sprint out of the turn.

Limitations

- Testing was limited to a single preseason period; results may not represent in-season performance or fatigue effects.

- Differences in team tactics, coaching, and technical execution may have influenced COD strategies.

- The study’s findings are specific to MRD-based testing (3 kg load); traditional timing-gate setups may not capture these phase-specific insights.

Coach’s Takeaway

- Coach the Approach ⮕ Focus on the athlete’s entry into the cut, focusing on rapid horizontal acceleration, appropriate approach speed, and controlled positioning before braking.

- Develop Braking Capacity ⮕ Train eccentric strength, isometric braking angles, and rapid eccentric force development through progressively loaded deceleration drills.

- Profile COD by Phase ⮕ Use MRD or other force-informed methods to assess Phase 1a time, Accel Max 1a, and Decel Max rather than relying solely on total 505 time.

- Individualize by Phase ⮕ Target an athlete’s weakest phase (approach, braking, or exit) when programming COD drills to make training more specific and effective.

I hope this helps,

Ramsey

P.S. I am developing the ultimate basketball performance course and certification program, backed by practical science-backed methods ⮕ Join Waitlist Here

Reference

Petway AJ, Harper D, Cohen D, Eriksrud O. (2025). Factors differentiating change of direction performance in NCAA Power 4 male basketball athletes. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching. doi:10.1177/17479541251360509.