The back squat is one of the most common strength exercises for building force, power, and resilience in athletes.

Yet subtle technical choices, especially at the very bottom of the squat, can meaningfully change the mechanical demands placed on the athlete.

One of those choices is bouncing out of the hole.

How does bouncing at the bottom of the squat alter ground reaction forces?

What Did the Researchers Do?

Subjects

- 36 trained lifters completed Session 1

- 29 completed Session 2

- Men and women with ≥2 years of squat experience

- All were resistance-trained and familiar with heavy back squats

Design

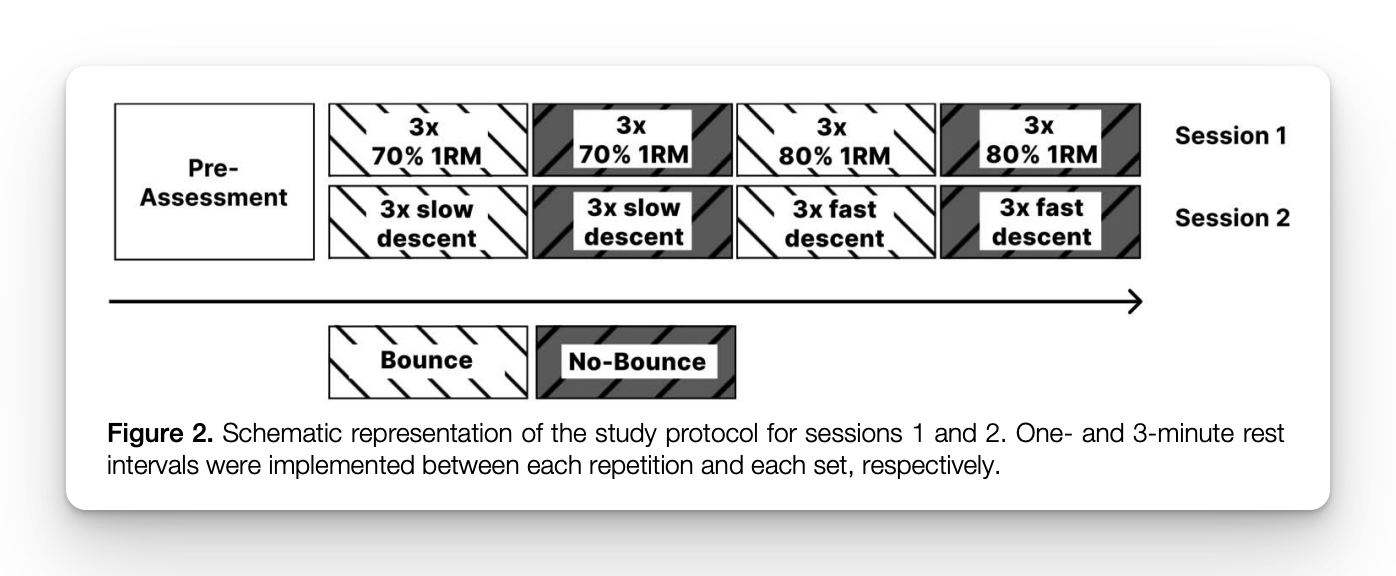

A within-subject crossover design with two testing sessions:

Session 1: Load manipulation

- 70% vs 80% 1RM

- Bounce vs no-bounce squats

Session 2: Descent velocity manipulation

- Fast vs slow descent

- Bounce vs no-bounce

- Load fixed at 70% 1RM

Key Definitions

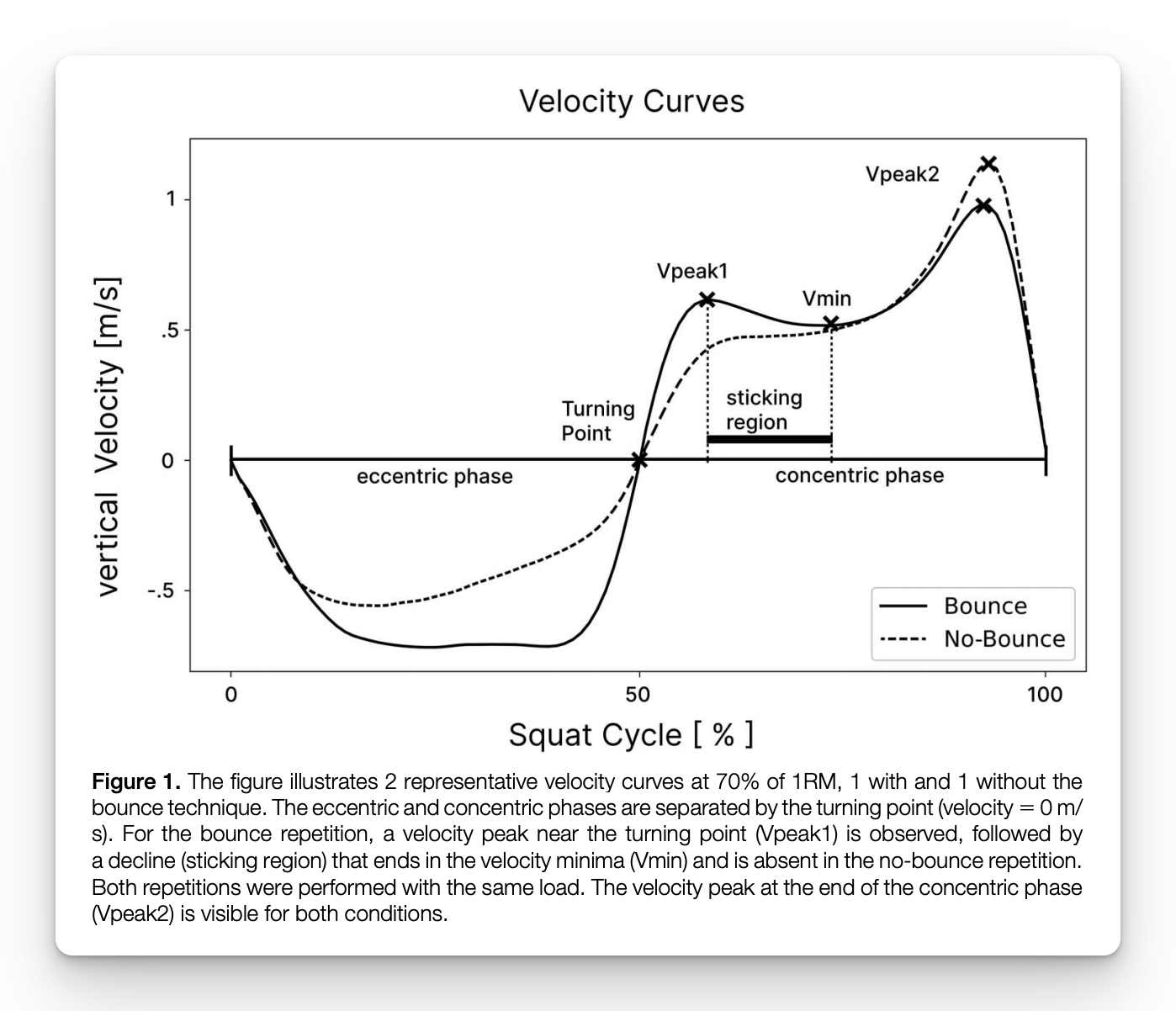

- Bounce squat ⮕ Actively accelerating into the bottom position to exploit the stretch-shortening cycle

- No-bounce squat ⮕ Controlled turnaround without rebound

Measurements

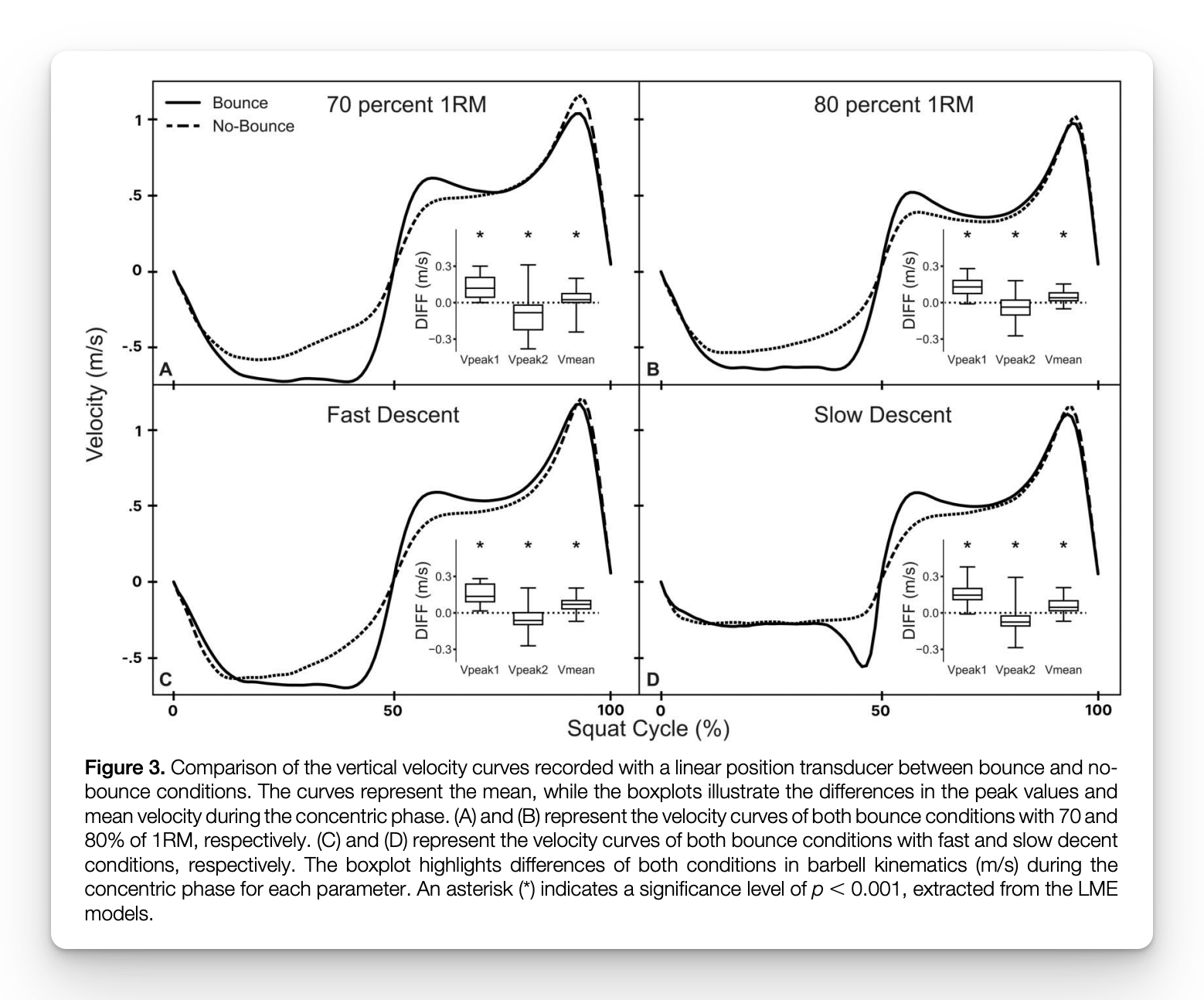

Ground Reaction Force (GRF) using dual force plates (1000 Hz) and barbell kinematics via linear position transducer (250 Hz), including:

- Mean velocity (Vmean)

- First peak velocity (Vpeak1, early concentric)

- Minimum velocity (Vmin, sticking region)

- Second peak velocity (Vpeak2, late concentric)

- Mean and peak power

What Were the Results?

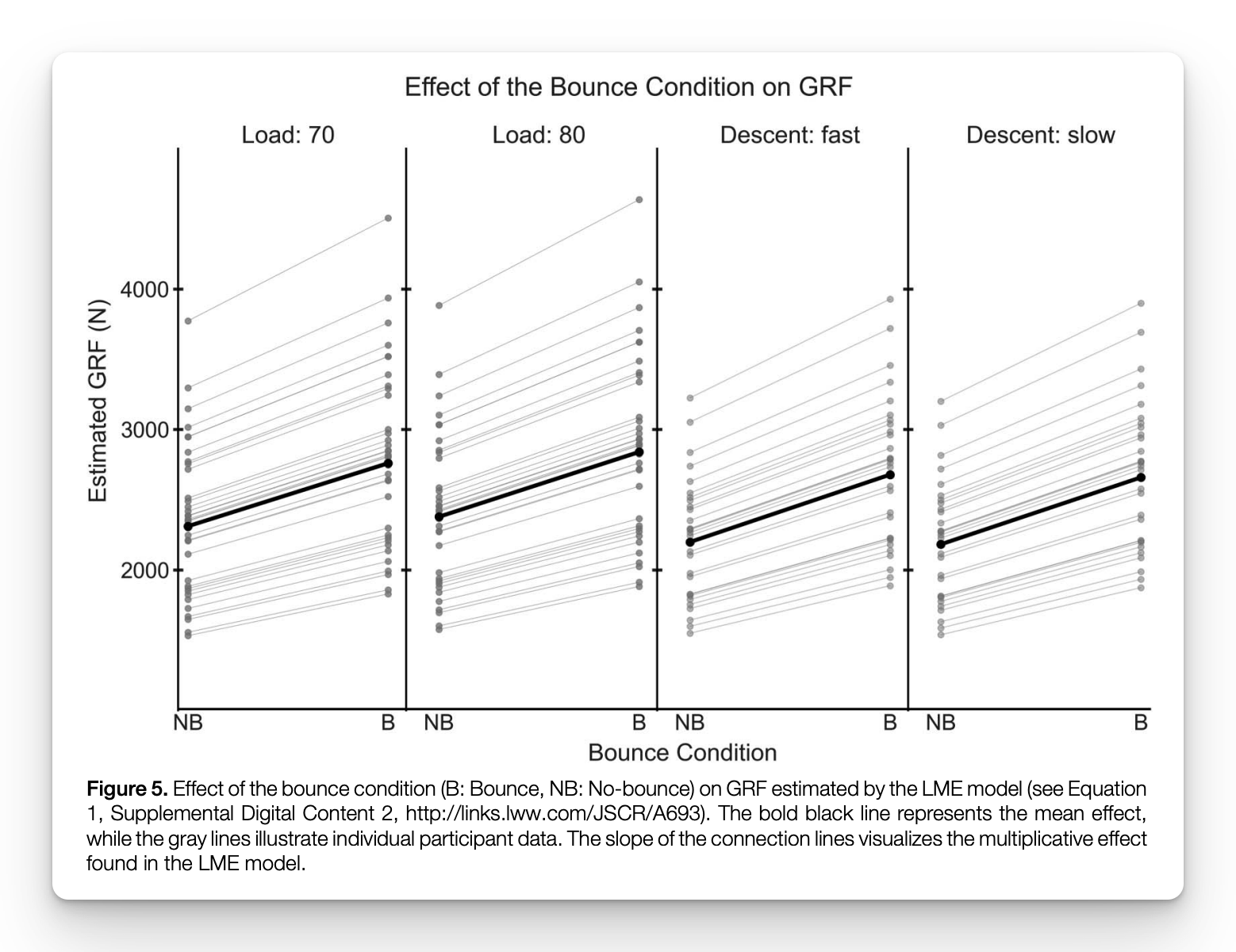

Bounce Squats Significantly Increase GRF

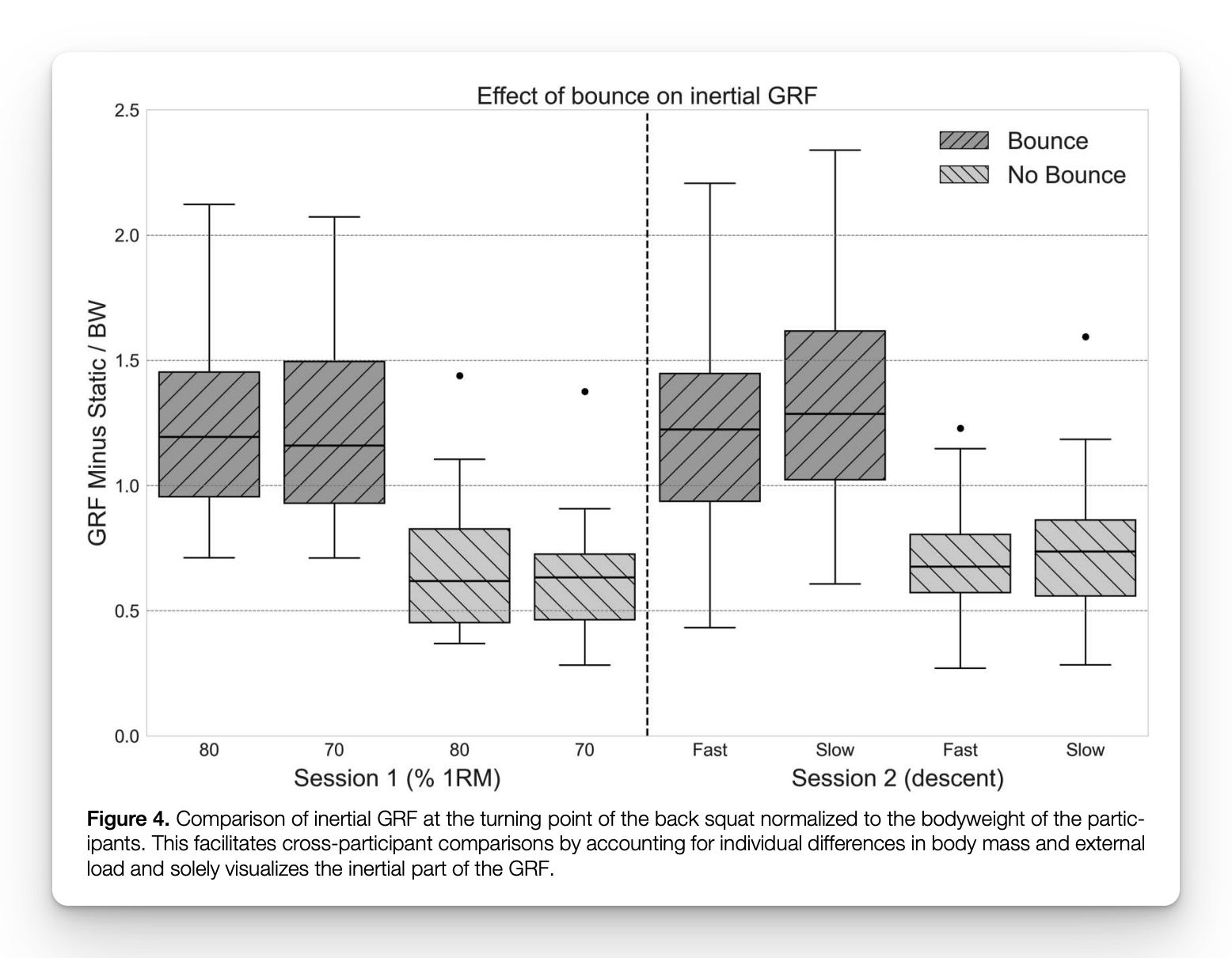

- GRF at the turning point increased by ~19% in Session 1 and ~22% in Session 2

- This effect was far larger than the effect of increasing load from 70 to 80% 1RM, suggesting technique mattered more than load for peak force exposure at the bottom

Bounce Shifts Where Velocity Is Expressed

- Vpeak1 (early concentric) increased significantly with bounce

- Vmin (sticking region) increased slightly

- Vpeak2 (late concentric) decreased

Heavier Loads Reduce Velocity, Barely Increase GRF

- 80% vs 70% 1RM has a small GRF increase (~3%) but clear reductions in all velocity metrics

- Load affected barbell speed more than force at the bottom

Faster Descent Alone Does Not Increase GRF

- No meaningful change in GRF

- No change in early concentric velocity (Vpeak1)

- Small increase in late-phase velocity (Vpeak2)

Importantly, descending faster is not the same as bouncing.

What Does This Mean?

- Bouncing substantially increases mechanical demand at the bottom of the squat

- Bounce enhances early concentric performance but may increase stress exposure

- Faster descent without bounce does not replicate this effect

- Load increases from 70 to 80% are relatively modest contributors to GRF compared to the technique

Limitations

- Squats were performed in a pre-fatigued state

- Acute effects only, no longitudinal outcomes

Coach’s Takeaway

Bouncing is a distinct mechanical strategy that trades higher force exposure for early-phase velocity gains.

- Technique drives force exposure more than moderate increases in load.

- Bounce increases early power but raises bottom-end stress so reserve this for healthy or late-stage rehab.

- A fast descent does not mean "bounce," and it won't replicate these alterations in kinetics.

I hope this helps,

Ramsey

Reference

Achermann, B. B., Drewek, A., & Lorenzetti, S. R. (2026). Acute effect of the bounce squat on ground reaction force at the turning point and barbell kinematics. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 40(1), 1–8.