Why It’s Time to Rethink the Metrics and Refocus on What Matters

Rethinking the Role of Training Load

Training load (TL) has become a buzzword in high-performance sports, plastered across dashboards, athlete monitoring platforms, and return-to-play protocols.

At first glance, it makes perfect sense: track how much work athletes do, and you’ll reduce injury risk, right?

Not so fast.

Despite widespread adoption, the belief that we can control injury risk through TL manipulation is more hopeful than it is evidence-based.

This guide will explain what TL can and can’t do, highlight where common metrics fall short, and provide a more grounded framework for applying TL monitoring in your injury-prevention strategy.

Let's dive in.

I’d like to mention that (1) my dissertation was done on the association between training load and injuries in the NBA and (2) I have nothing but respect for the many researchers in the space. This is not a criticism of anyone but a review of the litrature and a practical perspective to help coaches and therapist. Enjoy!

What Is Training Load?

Training load refers to the physical and physiological stress imposed on an athlete during training or competition.

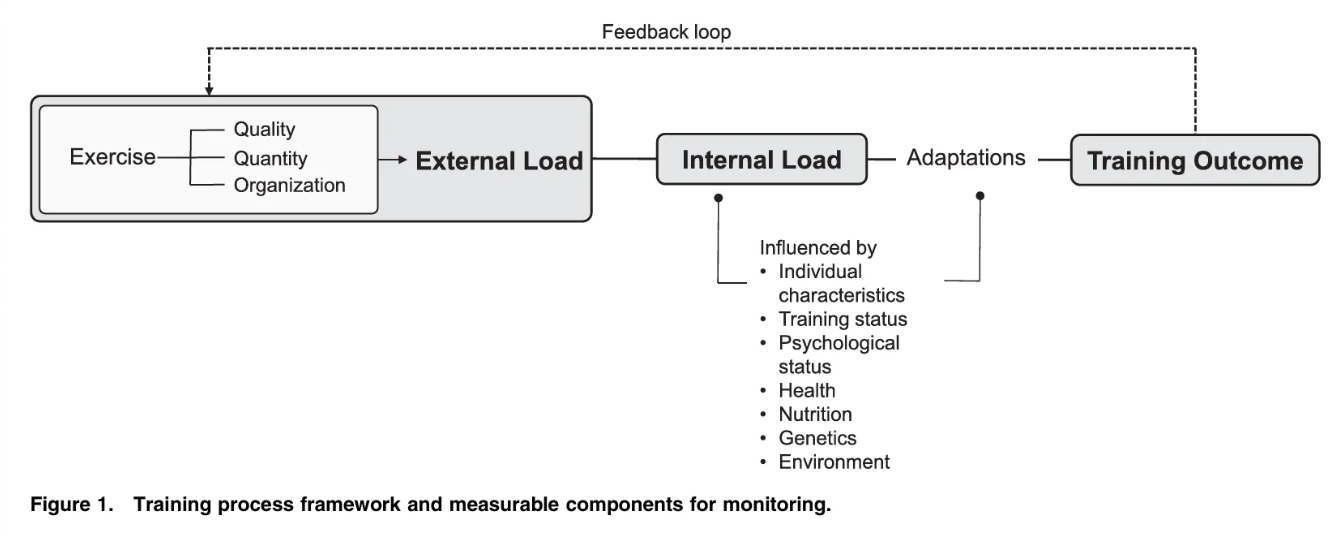

It’s typically broken down into:

- External Load: Objective measures like distance, weight lifted, speed, or accelerations.

- Internal Load: The athlete’s psychophysiological response to training—heart rate, RPE, blood lactate, etc.

TL is often used to verify whether athletes completed the prescribed work and to monitor how they responded.

Figure from reference 1

The Promise and Illusion of Predictive Metrics

Popular models like the Acute: Chronic Workload Ratio (ACWR) have gained traction for quantifying load progression and forecasting injury risk.

The logic is straightforward: track short-term versus long-term load and avoid “spikes.”

But here's the problem:

- These ratios don’t measure cause, only correlation.

- They fail to account for tissue-specific adaptation and individual context.

- Simulations have shown that even random data can produce “predictive” relationships with injury using ACWR.

- Arbitrary cut-offs (like the “sweet spot” of 0.8–1.3) have no biological basis.

The simplicity is partly why these ratios and sweet spots gained in popularity. However, they are too reductionist to account for the complexity of training adaptations and injury.

In short, many of the metrics we’ve leaned on are statistical illusions, not actionable science.

What Can Training Load Monitoring Do?

Used properly, TL monitoring can still be a valuable part of your toolbox.

Here’s where it shines:

- Verifying plan adherence – Did the athlete actually do what was planned?

- Tracking tolerance over time – Is the athlete handling progressive overload as expected?

- Identifying large deviations – Is an athlete under- or over-training compared to expectations?

- Informing adjustments – Alongside subjective and objective responses.

Think of TL like a dashboard gauge.

It tells you what’s happening, but it doesn't drive the car and cannot predict a crash.

Clinical Reasoning & Layered Decision-Making

Injury prevention is not a formula.

It’s a complex, interdisciplinary process.

Success comes from combining:

1. Evidence-based planning

Use training principles like overload, progression, and recovery timelines.

2. Athlete-centered monitoring

Include subjective metrics (e.g., soreness, fatigue), objective tests (e.g., jump performance), and contextual feedback.

3. Collaborative decision-making

Coaches, clinicians, and athletes should collectively make informed, individualized decisions.

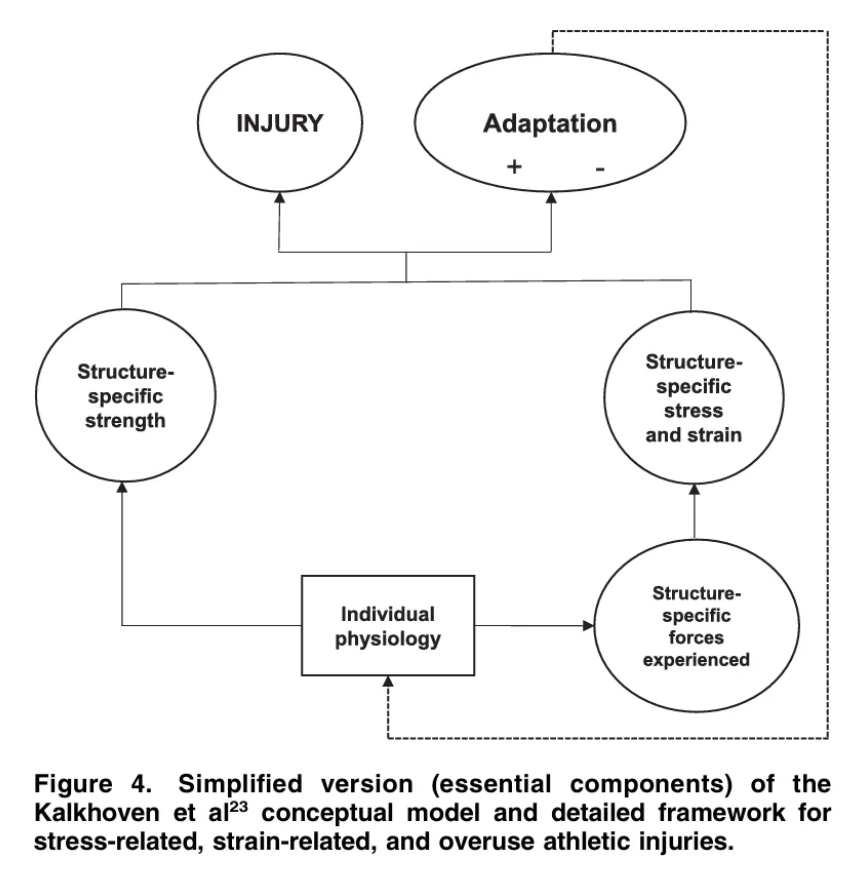

4. Focus on tissue-specific load tolerance

Build capacity across structures (bone, tendon, muscle) rather than chasing arbitrary numbers.

Figure from reference 1

The Risks of Overreliance on TL Metrics

Here’s what happens when we oversimplify complex systems:

- We ignore the multifactorial nature of injuries (e.g., biomechanics, prior injury, psychosocial stressors).

- We create false expectations with athletes, coaches, and organizations.

- We risk missing the real warning signs in favor of chasing “red zones” on a dashboard.

Worst of all, we may undermine the trust of athletes, staff, and the front office by promising control over something inherently uncertain.

This quote from Impellizzeri et al. (1) summarizes the risk of a TL-only approach to injury risk:

Most experts agree that injuries are multifactorial in nature, but if we place too great an emphasis on 1 variable alone (such as TL monitoring and manipulation), we are unlikely to succeed in appreciably and consistently reducing the injury rate. By using oversimplified, unilateral techniques to suggest we have the answer, we run the risks of both missing out on the opportunity to identify other factors that may contribute to injury and leaving stakeholders unimpressed when injury rates fail to decrease by the promised amounts.

How to Use and Not Use Training Load

Let’s be honest: we can’t eliminate injury risk.

But we can reduce it through intelligent, adaptive planning.

Training load data can be incredibly useful when applied appropriately, but it’s just one piece of the performance puzzle.

Here’s how to think about it:

Use TL to:

- Track adherence to training plans

- Inform decisions alongside other metrics like movement quality, readiness, and recovery data.

- Adjust load based on athlete feedback and observed tolerance over time.

- Support return-to-play readiness by monitoring gradual progression and identifying deviations.

Don’t use TL to:

- Predict injuries with precision

- Assume control over complex systems

- Replace judgment with algorithms

- Oversimplify communication with stakeholders

The bottom line: Training load is a support tool, not a silver bullet.

It works best when used in context, combined with clinical reasoning, and always filtered through the lens of the coach’s experience.

Context Matters: Injuries Don’t Happen in a Vacuum

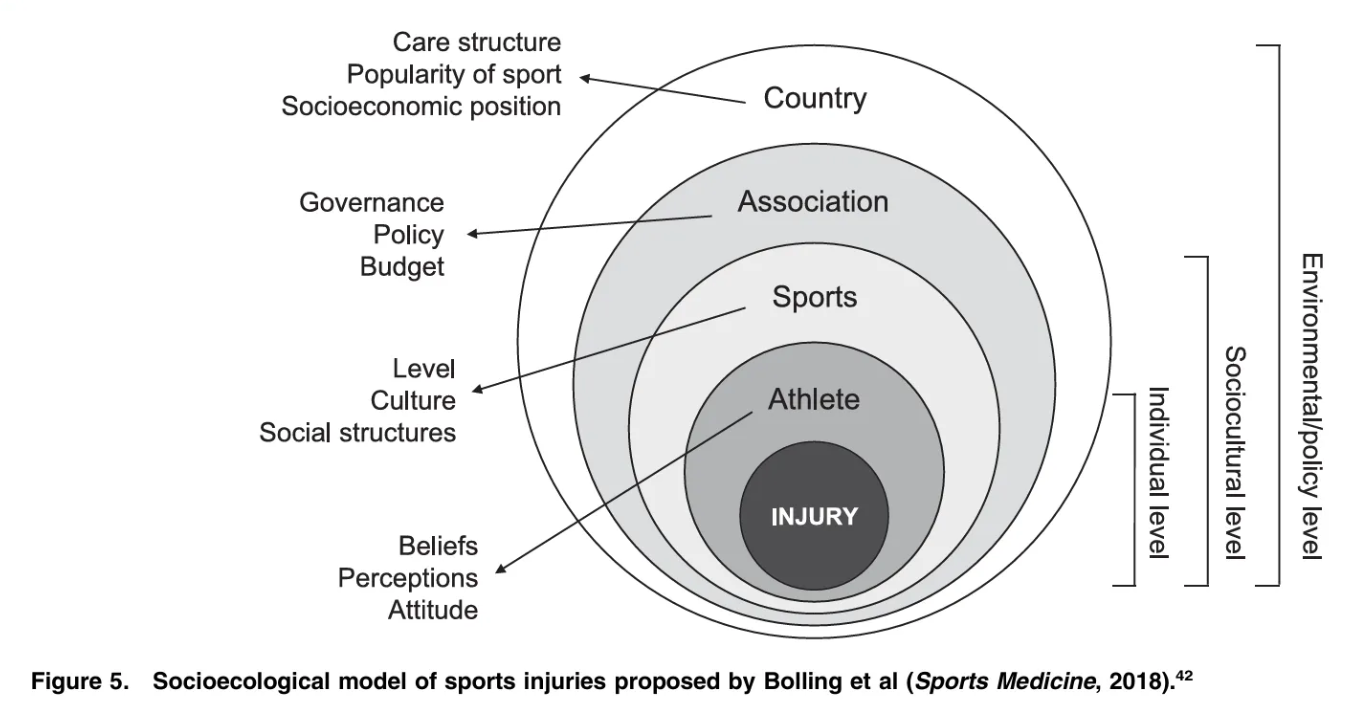

To fully understand and reduce injury risk, we must look beyond the athlete and recognize that multiple layers of influence shape injury.

Not just what happens in training.

The Socioecological Model of Sports Injuries (Bolling et al., Sports Medicine, 2018) visualizes this beautifully.

At the center is the injury itself, but wrapped around it are several interconnected layers that build the injury (and performance) context:

Individual Level

- Beliefs, attitudes, and perceptions about injury, pain, and recovery.

- Athlete behavior, risk tolerance, and willingness to report symptoms.

Sociocultural Level

- Team culture, norms, and communication.

- The way performance staff and coaches structure return-to-play decisions.

- Social pressure to “push through” or downplay warning signs.

Environmental / Policy Level

- Sport organization policies, resources, and governance.

- Scheduling, travel demands, and support staff infrastructure.

- The broader socioeconomic context and care structures of the country or club.

This model reminds us that:

- Injury is rarely the result of just one thing.

- Training load is only one small piece of a much larger system.

- We must account for psychological, social, cultural, and policy-related forces.

TL in isolation will never fully explain injury risk.

It’s not just about what athletes do; it’s also about how and why they do it and the environment they do it in.

Figure from reference 1

Takeaways for Coaches & Practitioners

Here are 5 key takeaways to help you cut through the noise, use training load more effectively, and build a smarter injury-prevention strategy.

These are the principles that should guide how you interpret and apply TL in the real world.

1. Training load is a tool, not a solution

Injury is never monocausal. ACWR, weekly volume, or spikes alone can’t tell the whole story.

- TL metrics help you track what was done but not why or how an athlete responds.

- Use them as a compass, not a GPS.

- They should support decisions, not dictate them.

- Never let a ratio replace coaching instincts, conversations, or athlete feedback.

2. No single metric can predict injury

The best injury decisions come from layered thinking:

- TL data

- Athlete wellness

- Movement quality

- Recovery patterns

- Contextual factors

Instead of trying to eliminate risk, focus on managing complexity.

3. Return to training fundamentals

Simple doesn't mean easy.

Build robust athletes by:

- Gradually increasing tissue tolerance.

- Prioritizing movement competency under load.

- Programming with purpose, not pressure to meet arbitrary numbers.

Consistent application of progressive overload, recovery, and adaptation still wins.

4. Broaden your view beyond training

The socioecological context matters.

Your injury prevention strategy should include:

- Open athlete dialogue.

- Clear expectations.

- Aligned priorities across staff.

Culture, communication, and care systems influence injury as much as training.

5. TL doesn’t prevent injuries, but coaching does

Technology and data can guide us.

But it’s coaches and practitioners who:

- Ask better questions.

- Recognize patterns.

- Adjust training based on human nuance.

Keep TL in the toolkit, but build your injury-prevention strategy on relationships, reasoning, and real-world readiness.

References

- Impellizzeri FM, Menaspà P, Coutts AJ, et al. (2020). Training Load and Its Role in Injury Prevention, Part I: Back to the Future. Journal of Athletic Training, 55(9):885–892.

- Impellizzeri FM, McCall A, Ward P, et al. (2020). Training Load and Its Role in Injury Prevention, Part II: Conceptual and Methodologic Pitfalls. Journal of Athletic Training, 55(9):893–901.

- Bolling C, van Mechelen W, Pasman HR, Verhagen E. (2018). Context matters: revisiting the first step of the “sequence of prevention” of sports injuries. Sports Medicine, 48(10):2227–2234.